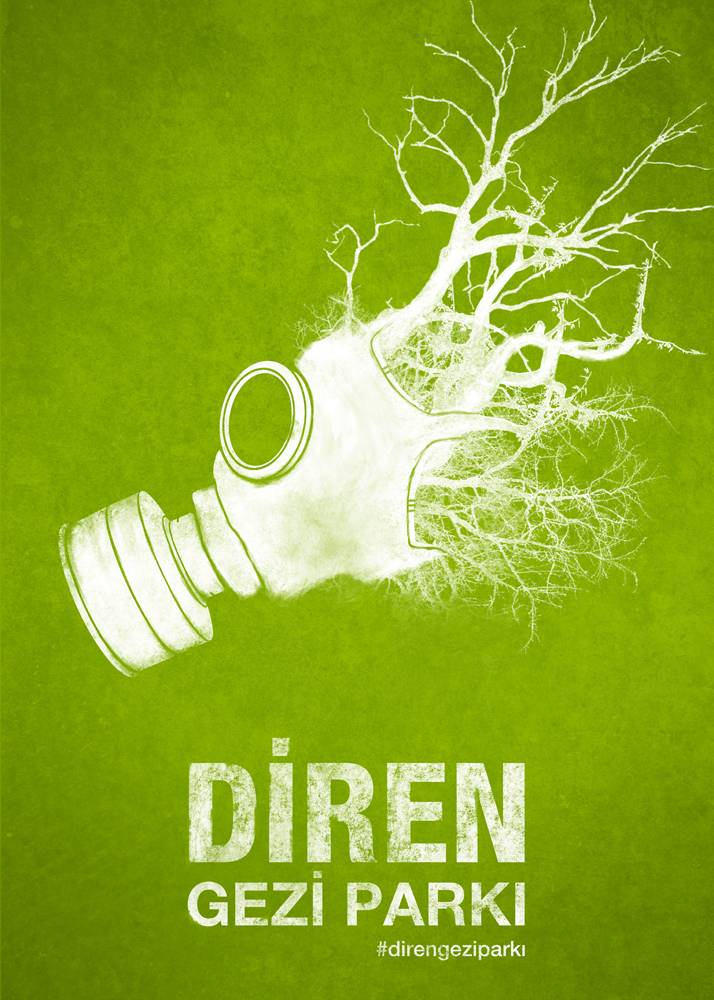

Interview on Gezi Uprising in Turkey

During and after the Gezi Uprising, or the June Uprising as we sometimes say, many comments were made by some intellectuals and columnists, indicating that this uprising meant a complete break from the former historical movements in the country.

This half-baked argument was an attempt to isolate the mass of the protesters from the socialists and from their tradition of resistance that dominates the history of popular uprisings in Turkey with its important days, historical figures and symbols. And after the Uprising, we have seen other attempts to back this argument with so-called ‘social-class analyses’ that limited the scope of uprising with Gezi Park and the protesters with mainly from those of petit-bourgeois origin.

It would be enough, however, to remember that by 2007 radical socialist organizations renounced the government ban on Taksim Square and declared that they will celebrate the May Day there from then on at any cost. After struggling for 3 years to break the siege, the AKP government was eventually defeated and forced to abandon the Square in 2010.

The people’s anger against the AKP government was becoming so strong that the May Day of 2012 in Taksim Square, which was one of the biggest May Day demonstrations around the world with approximately 1 million people, was turned into a massive protest against the government. AKP government was really afraid and placed a second ban on the Square in 2013 to prevent another May Day celebration.

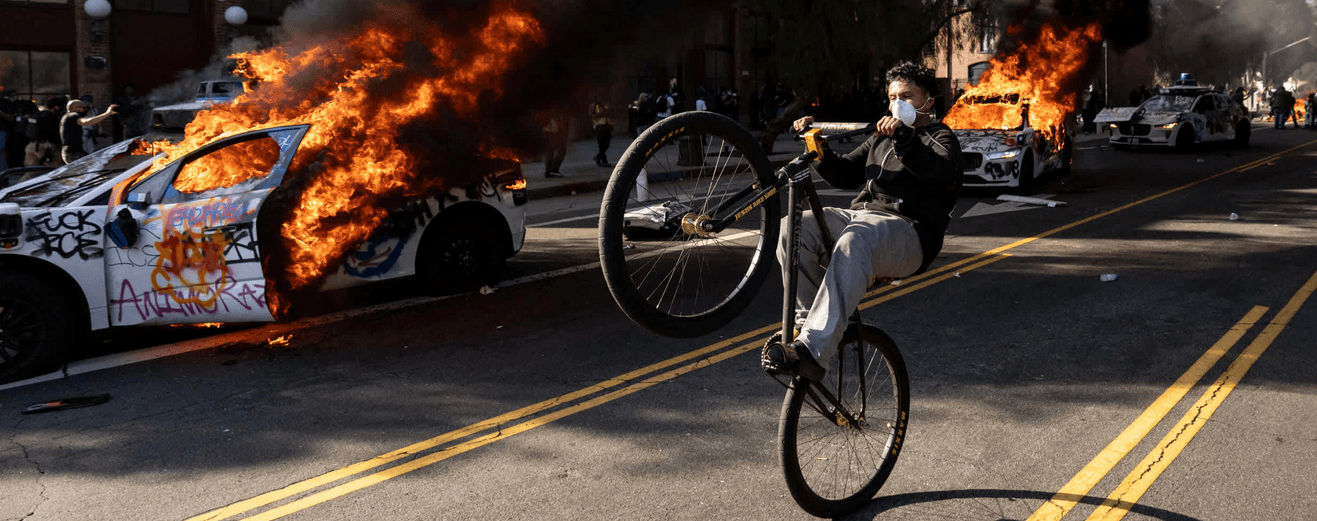

Therefore, just one month before the June Uprising the police forces of the state literally laid a continuous siege on Taksim Square, prevented any group of people from going in and this led a series of daily protests that ended up with tear gasses and water cannons unexceptionally until the Uprising began.

I am not trying to reduce the June Uprising to one of its aspects; but this short-term historical background is always forgotten to the price of emphasizing the novelties of the movement, which is also very important. The avalanche started because there was too much snow already.

The Uprising created a new political environment where the former self-confidence of the oligarchy perished and the people became more daring. Before the uprising, you could see the hopelessness in the eyes of some people. Apart from the revolutionary left-wingers and the Kurdish opposition, most of the members of the popular classes seemed to be tired and uninterested with politics.

Right after the Uprising, however, popular assemblies who named themselves as “Forums” started to flourish around the country, gathering people from the same neighborhood around common problems. Although most of them are inactive and unable to institutionalize themselves for now, it was a unique experience on our behalf. And some of the ongoing forums still serve as communication centers, making calls for the future protests.

It has ups and downs, but I can say that relatively almost every week there are protests in Turkey somewhere most of which end up with clashes with the riot police.

The clash scenes are important for the young militants who find the opportunity to understand the dynamics of the masses, to gather first-hand experience at the barricades. You can say that a new generation of young revolutionaries is training themselves in the midst of action.

There is another novelty, however, which is overlooked most of the time in the fog of the ongoing crisis: The workers’ actions. Towards the end of June, a group of workers occupied a factory in Istanbul –a move clearly inspired by the Uprising– and declared themselves as the real owners of it. It was a textile factory producing shirts and sweaters.

After solving the problems with the police and the courts, now since June 2013, the workers of Kazova are operating their own factory, dividing their income equally among themselves, which happens only for the second time in the history of the country.

The workers are not giving a hard time to the capitalists only. The managers of a reformist labour union named Confederation of Revolutionary Labour Unions (DİSK) are also feeling the pressure of gradually radicalizing workers movement. The workers from different sectors occupied the DİSK Headquarters 4 times in last 6 months to protest the collaborationist policies of the union.

Another important novelty was that the oligarchic bloc that has been ruling the country for nearly 12 years dissolved shortly after the Uprising. And since 17th of December we see an internal conflict inside the state apparatus. The parties of this conflict started relentlessly to expose each other’s crimes against the people to discredit each other. And this had a serious impact on people’s already waning confidence to the state authority.

As I have said, during and after the Uprising people tried to form popular assemblies in their own neighborhoods and although it was a very important step, most of them are inactive now.

The ideological diversity of the Uprising seemed to be what made it powerful, but soon it stopped being a secondary problem and presented itself as the main obstacle. But everybody knows that the solution to the problems of struggle is to struggle more.

I think this is the problem of all revolutionary struggles, to get organized, and if there was a simple solution, the socialists would find and apply it long ago. This is the problem we face in Egypt, in Spain in Tunisia, wherever there is a popular uprising.

The problem is that the oppressive regime in Turkey has been blocking all the attempts towards a peaceful change for a long time. An Associated Press survey showed that Turkey has the biggest political prisoner population around the world. And since the Uprising, the government is tightening its grip over the people, incessantly raiding houses, arresting people, issuing new oppressive laws and recruiting new policemen.

So we don’t have dreams about uninterruptedly growing peaceful popular organizations that will eventually bring a democratic change.

That is why I am very critical against some attempts to lead the potential of the Uprising towards electoral politics. Various left-wing political parties and groups aligned themselves to the parliamentary politics of a reformist pro-Kurdish party, Peace and Democracy Party. These parties and groups formed an ‘umbrella party’ named People’s Democratic Party and they are preparing to run in the local and general elections.

They have democratic demands that nobody can reject, that is for sure. But for the peoples of Turkey, the current regime has long lost its legitimacy. It is not just an issue of electing this or that bourgeois political party. The regime itself is corrupt and it is utilizing the ballot box to legitimize itself. I believe the socialists should not play a part in this democratic game of reestablishing the regime’s legitimacy.

Because the country is in a serious crisis and it is possible to turn it into a revolutionary one.

It is impossible to talk about a single approach that would characterize the Uprising’s position against the Kurdish people. I have spent some time in the western coast of Turkey, in İzmir during the first days of the uprising and saw that nationalist groups were trying to physically attack the Kurds and socialists who were in the same protest with them.

We have also seen in Ankara and İstanbul that republican nationalists, Kurds and socialists resist and dance shoulder to shoulder. The posters of Mustafa Kemal and Abdullah Ocalan, who were completely unbearable figures for the other group, were placed side by side. The tolerance was there.

But as I said, it would be an illusion to think that the ideological differences could be overcome in just months. The regime knows that the Kurdish question can easily divide the society into two hostile camps and will never give up using this to its own advantage.

It is still possible to talk about three main different opinions regarding the Kurdish question.

First group is the nationalist and Kemalist one, who strictly rejects to recognize the existence of Kurdish people. Almost everywhere, they failed in dominating the Uprising and its aftermath. Their political line does not occupy a serious place at least for now but remains as a potential that could be mobilized if the ruling classes consider it as necessary.

Second opinion is also the dominant opinion. It is a moderate approach that recognizes the existence of Kurdish people and says a peaceful solution must be found to put an end to this a century long problem. They demand the fundamental democratic rights for the Kurdish people. This line of thought became powerful after the peace negotiations between the Kurdish movement and AKP. This is also the reformist political line adopted by the pro-Kurdish Peace and Democracy Party and its new umbrella form People’s Democratic Party.

The third position is adopted by the revolutionary elements of the Gezi Uprising. What they say basically is that the current regime cannot bring democracy even to the Turkish people, let alone the doubly-oppressed Kurdish people. According to them, there is a need for a revolution even for the fundamental rights of the people (like right to self-determination of Kurdish people) and workers because the regime is becoming more and more oppressive and greedy as the crisis deepens.

They claim that it would be misleading to nurture hopes of a peace between the peoples in Turkey and the regime, because the regime is already in a war against the peoples of the country.

It is a question that many people ask themselves in Turkey. Some political parties try to impose their representative political vision into the movement, hoping that they would mobilize the energy of the Uprising.

However, no such political perspective can claim to represent the diversity of the protesters for now. The entire uprising and the ongoing crisis themselves were partly a reaction against this straightjacket called representative politics imposed by the capitalism.

But if a political party wants to really represent the people in Turkey, it should be in the forefront, in the middle of the class struggle. The current divisions, the existing ideological disunities among the people are the results of the weakness of the class struggle. It is natural that those who do not struggle for socialism will end up struggling for themselves.

If a political party really wants to become the representative of the interests of the people, it should lead the way, if there is no way it should pave one, as Lenin said. It has a heavy price but eventually the people will follow.

That’s what I think.

Ti è piaciuto questo articolo? Infoaut è un network indipendente che si basa sul lavoro volontario e militante di molte persone. Puoi darci una mano diffondendo i nostri articoli, approfondimenti e reportage ad un pubblico il più vasto possibile e supportarci iscrivendoti al nostro canale telegram, o seguendo le nostre pagine social di facebook, instagram e youtube.