“A fistful of dripping hate” Intervista a Phil A. Neel (Eng version)

Trumpism, war and militancy

The year 2024 has been dense with significant events. Complexity is in motion, we see it accelerating in political transformations, electoral or otherwise, in the winds of war blowing across the globe, in social and political phenomena that are increasingly difficult to interpret with traditional keys.

To try to provide us with some more enlightened tools for interpreting the present, we interviewed Phil A. Neel, communist geographer and author of the book “Hinterland. America’s New Landscape of Class and Conflict.” His book is one of the most interesting reconstructions of the relationship between value chains, political geography and class composition in the United States leading up to the first election of Donald Trump. Not only that, the interpretation of contemporary capitalism, globalization on which “Hinterland” rests is solid and offers many insights that transcend the specificity of the US context.

We have divided this interview into three sections starting with Trump’s re-election, then expanding the argument to the global context and finally touching on some issues related to militancy.

Enjoy your reading!

Trump’s re-election

How has Trump’s coalition changed, if at all, in these four years?

Well, there are two slightly different questions here. The first is about the Trump coalition, which is to say the elite forces backing his bid for president. And the second is about people who just voted for him, which is obviously a much broader group. As for the first question, the base of support for Trump hasn’t really shifted. Mike Davis has a great analysis on this from the 2020 election, which remains the most important commentary on Trump. Davis argues that, in addition to the normal institutional supporters of Republican bids such as energy interests and defense contractors, the real foundation of the Trump coalition could be found among “lumpen” bourgeois interests “largely peripheral to the traditional sites of economic power” and concentrated in “hinterland places like Grand Rapids, Wichita, Little Rock and Tulsa, whose fortunes derive from real estate, private equity, casinos, and services ranging from private armies to chain usury.” These are, in other words, the minor fiefdoms ruling from “micropolitan statistical areas,” which are often exurban in character, or which serve as the closest thing to a “city” in mostly-rural regions.1

A particularly useful illustration is the role of auto dealers, selling (mostly used) cars directly to consumers. This is the sort of job that people often see as a basically “working class” enterprise, similar to small businesses run by construction contractors. They produce nothing and are, essentially, just commercial intermediaries. But, in fact, both auto dealers and construction contractors are among the most common professions in the top 0.1 percent of US earners, making more than $1.58 million per year. As for car dealerships, more than 20% of these are owned by individuals making more than $1.5 million.2 These are certainly not the major capitalist interests by any means, and they in fact often have interests that conflict with those of “big business.” Nonetheless, there is no ambiguity that these are businesspeople and that they therefore constitute a segment of the bourgeoisie. However, although they have absolutely no real connection to the working class, their “lumpen” character nonetheless confuses naïve urban liberals, who tend to read class through cultural signifiers and technical credentials. So these businesspeople appear to be a “white working class” because they maybe only have a high school education and wear Carhart jackets (which of course are always a little too clean). In Hinterland, I therefore referred to these lumpen bourgeois interests as the “Carhart Dynasty.”

So have there been any major changes to this coalition in the past few years? Not at root, no. However, the demonstrated power of this base has begun to attract a growing number of politically-minded industrialists and political strategists advocating things that certainly resemble the early stages of a classical Fascist political program: thus figures like Musk, Thiel and libertarian billionaire Jeff Yass (a prominent investor in TikTok and funder of far-right think tanks in Isreal) have joined established supporters such as Timothy Mellon and Miriam Adelson. This was also visible in the scandal over Project 2025, penned in part by Kevin Roberts, a strange quasi-Falangist Catholic who replaced more traditional conservative Kay Cole James as president of the Heritage Foundation in 2021. Trump himself, however, is somewhat ambiguous in this regard and, contra hyperbolic fears that he will nullify democracy, the inertia of established ruling class institutions will most likely see his second administration trend toward the norms of US governance much like he did in his first administration. Those who portray Trump as a “fascist” just water down the term. He’s basically your average conservative white baby boomer.

What about the social composition of his electorate?

I’ll answer this with some caution, since it’s a bit too early to say with much confidence exactly what shifted and where—we still don’t have the most reliable data and are only working with polling information. Nonetheless, only about 64% of the eligible population voted, which is lower than in 2020 but still historically high. Notably, Trump won the popular vote, becoming the first Republican candidate to do so in decades. But also remember that only about 245 million people were eligible in the first place, which is about 70% of the US population of 335 million. The ineligible remainder are either minors who cannot yet vote, felons who have been stripped of the right to vote, or immigrants who have never had a right to the vote in the US. So, as in any US election, the decision was actually made by less than half the population. And studies have consistently shown that the poorest of eligible voters are the least likely to vote, so the data is always biased upwards. For example, in the 2022 midterms, about 58% of voting-eligible homeowners voted, while only 37% of eligible renters did. In the same election, about 67% of eligible voters with incomes above $100,000 voted, compared to just 33% for those with incomes under $20,000.3 So, as in every election, I always implore people not to conflate voting data with raw demographics: if X percent of Hispanic voters, for example, cast a ballot for Trump, it does not mean that X percent of the Hispanic population supports Trump. If voting data demonstrates anything, it tends to demonstrate ideological shifts among the wealthier strata and changing patterns in non-voting among the poorer strata.

That said, it does appear that two major shifts occurred: many wealthy (100k+) voters shifted to the democrats and the collapse in the Democratic voter base below that income level led to the appearance of increasing support for Trump among the lower income brackets. These are not actually shifts “toward” Trump, however, since they are caused by the hemorrhaging of Democratic votes overall, particularly in states like Texas and Florida. And, contra the “Trump Country” narrative that counterposes a Democratic city to a Republican countryside, the collapse of the Democratic base also saw them lose millions of votes across all metro areas, including in the center of large cities. Insofar as any of these things were caused by a “gain” in votes for Trump, the gain appears to be marginal. Where does an actual shift toward Trump appear to have occurred? Possibly among wealthier non-white voters, particularly Hispanic voters. This shift seems to exceed that caused by the collapse of the Democratic base. In part, this was a continuation of trends already visible in earlier elections, centered on border territories like the Rio Grande Valley in Texas. But, in this cycle, it also extended to core urban areas in places like Philadelphia.4 And it’s not surprising. Something like this has been predicted in studies of US immigrant populations for decades and anyone following the evolution of the far-right in the past 30 years has noticed the same trend.

In Italy, the mainstream media, mostly of liberal orientation, treated the events on Capitol Hill as collective madness or an attempted coup d’état and quickly deleted them afterward from the newsfeed. Trump was given up for finished politically. What did they mean instead in the United States, outside the world of institutional politics and the media? What were the different reactions among ordinary people?

It was a very confused event, more a carnivalesque farce of insurrection rather than the real thing. But who knows. If rightwing forces gain more power in the future, maybe the event will be seen as something similar to the Beerhall Putsch: the farce prefiguring the tragedy, rather than the other way around. Those who thought that this indicated that Trump was “finished” simply don’t understand how politics works. They believe the liberal myth that those endowed with state power are required to exhibit a certain cordiality, which of course has never been true. Their attitude toward the criminal case against Trump was similar, believing that a felon could never be elected President. Ultimately, you have to remember that liberals are the type of people who put a lot of stock in things like the value of credentials, education, clean records: all the hollow cultural signifiers that can distinguish you from the working class. To them, the storming of the Capitol can only represent an inconceivable madness afflicting the body politic and signaling the breakdown of the hierarchies that are supposed to structure any reasonable society. And, in fact, it is in this attitude that we might find the genuine germ of Fascism, rather than in the confused scrawls left on the halls of Congress.

In Italy, the key word to explain Trump’s victory is inflation. “Perceived” or real depending on the political orientation of the commentator. In a 2022 article you explained that inflation is nothing more than the epiphenomenon of something deeper within contemporary capitalism (we translated this article). Two years later what assessments would you add?

And yet in 2016 Trump was elected in deflationary conditions, when interest rates were at or near the lowest they had ever been. So, this can’t be the whole picture. The inflationary wave certainly played a role in what is conventionally described as “economic anxiety,” and anger over the state of the economy was a central factor in the election. But Trump didn’t really offer any program for reducing inflation. In fact, if his proposed tariffs are implemented, they will almost certainly ignite a new round of inflation. Rather than agitate on the issue, he simply channeled this anger toward easier targets. In fact, the most remarkable thing about this election, in my opinion, is how neither party put forward essentially any program whatsoever. Trump simply rambled about immigrants, gestured toward China, and pushed all the correct culture war buttons. More importantly, he stoked righteous anger over economic problems being faced by basically everyone making less than six figures. Meanwhile, Biden and Harris did little more than pat themselves on the back, seeming to earnestly believe that their existing policies were widely recognized success stories, and thereby proving themselves yet again to be completely detached from reality.

Imagine for a moment that you’re just an average American going to grab something from a drugstore. Imagine that you’re nowhere special: not in any of the big coastal metropoles or in the conservative “micropolitan” towns. Maybe one of those great, flattened cities that sprawl across the southern deserts. So you go into this Walgreens and let’s say you’re in Albuquerque, where the first thing you’ll see is one of the heavily armed guards dressed in olive green military fatigues deployed by the private security company hired by businesses throughout the central city. You pass the smiling mercenary and navigate through the line of maybe a hundred people waiting for hours to access the understaffed pharmacy where they’ll ultimately be told that the insurance company won’t cover the costs of the medicine prescribed by their doctor because it failed to gain a prior authorization ordered by the insurance company to keep down its costs. Maybe you overhear some of them chatting in line about how they’re worried their building will be sold to some real estate developer from Santa Fe who wants to triple the rent or how they had to flee homes destroyed by the devastating fire in Mora, and still haven’t received their FEMA payout. Others unconsciously rub at injuries suffered during 10-hour shifts at the Amazon warehouse just West of town near the border of the Pueblos, pockets full of ibuprofen.

You’ll make your way through the aisles, noting that every single toothbrush and tube of toothpaste is behind bulletproof glass. So is the candy, the laundry detergent, and of course the baby formula. The lone staff member is running back and forth from the registers to unlock different sections of the store, breathing heavy and about to collapse, and you can smell that subtle hint of ammonia on their sweat that hints at an endocrine disease—those plagues that have a special affinity for the poor. The thing that you came for is out of stock, as are any number of items, leaving nothing by empty cells with a price tag behind the glass as if the very air would cost you. You grab a bag of chips for no particular reason, and you wait for the cashier to return from their run, keys jangling like chains. After tax, the bag of chips costs you nearly a full hour’s work at the national minimum wage. Then imagine seeing these two campaigns: the Democrats congratulating themselves on their well-run administration that has seen “historic gains” for “working people,” and the Republicans doing nothing more than dipping a hand down into that deep, dark, well of blood that lies underneath the continent, drawing up a fistful of dripping hate.

So yes, inflation plays a role here, but it’s really only a small part of what’s going on. Housing costs were inflating even in the “deflationary” era. And, in fact, there’s a huge divergence between “felt” inflation in the common purchases made by people in everyday settings (like gas, food, shelter, etc.) and “core” inflation that tries to measure a “healthy” price level within the economy as a whole.5 And, as the article you mention explains, inflation is itself an epiphenomenon of larger changes occurring within global production.6 The most important of these are what I call the “regionalization” of global production, which is often mistaken for “deglobalization” but is in fact mostly a matter of trade growth between China and the US stagnating while trade growth with “nearshore” partners is skyrocketing, especially across Eurasia. The result is a regionalization of production networks, with each region reintegrated into global production networks in novel ways. So, for example, supply chains in China have not really become less important—there’s really been no “delinking” of China in the US in any legitimate sense—but they are now also routed into assembly lines in South and Southeast Asia, Mexico, and Eastern Europe. And the suffering that poor people are facing here in the US is obviously connected to these changes as well. The increased tariffs imposed by both Trump and Biden, combined with rising wages in China and the raising of interest rates after the pandemic, have served to further undercut the de facto subsidy Americans enjoyed during the decades of globalization, when stagnant wage growth was tolerable solely because it could be made up for with cheapened goods and free-flowing credit. The Great Recession marked the first stage of erosion for this subsidy and the post-pandemic crisis marks the second.

So are you saying that the Biden administration’s turn to “industrial policy” visible in things like the Inflation Reduction Act has proven ineffective, and this is part of why Trumps economic platform proved popular?

Not quite. It’s debatable what effect these new Biden-era subsidies have had but it’s clear that in certain sectors they’re quite effectively generating new investment. But that’s not really the issue. The problem is that neither party has put forward any program or plan that has proven capable of actually generating much employment or growing real wages—nominal wage increases after the pandemic were entirely eaten up by inflation. Trump promised to bring tens of thousands of factory jobs to Wisconsin via a deal with Foxconn that was, in no way shape or form even remotely possible because it was simply not profitable. It is still not profitable to produce most goods in the US, especially goods that require large amounts of unskilled labor. And it is certainly not profitable to do so if you want to offer anything even close to a living wage. So, what did the big promised Foxconn factory in Wisconsin actually become? Microsoft buys the land eventually and turns it into a data center employing a small handful of people.

That then marks the shift to the Biden era policies, which saw limited “success” in selectively stimulating new investment via measures such as the Inflation Reduction Act precisely because these policies targeted the low-employment sectors where investment was already more likely. Most of the new investment stimulated by these policies has therefore been in the lowest-employment sectors such as battery production. In other areas, like EV production, the subsidies have certainly helped major car manufacturers expand capacity, but this also effectively downsizes production in employment terms, since EVs require, on average, fewer workers to produce. While these plants look to be employing more workers initially, this has more to do with the higher labor utilization rates common in the early stages of production and with greater vertical integration, making more of the employment visible because more of the people doing the work are directly employed by the company rather than by subcontractors.7 In other words, the revival of industrial policy has been able to address certain aspects of the investment problem precisely because it ignores the deeper problem of employment.

Can you elaborate on this problem of employment? It seems to relate to larger issues you discuss in your work, such as the question of “surplus population.” Is there really no chance that these new industrial policies will bring back manufacturing jobs?

We can subdivide the issue into three different aspects. First is absolute immiseration, visible in long-term unemployment and forms of extreme abjection such as imprisonment, homelessness, and all the people fleeing conflicts and environmental catastrophes who compose an enormous share of the migrant population. When people think about “surplus population,” which is now a pretty well-known Marxian concept, these extreme examples are usually what they are thinking of. And it’s not quite wrong, it’s just not the whole truth. Because the “surplus population” is much, much broader than this and these examples are, in most places, still exceptional cases that don’t represent the norm—even if the number of people exposed to this sort of absolute abjection is also growing. To the extent that Trump and Harris offered any sort of policies meant to address the employment crisis, they largely offered punitive solutions: mass deportations, a strengthening of border controls, and the suggestion of even more aggressive anti-crime policies. Even in “liberal” California for example, we also saw a number of aggressive “anti-crime” measures passed and a proposition to ban prison slavery rejected.

Second, we have “underemployment” of various sorts, which would include people with precarious jobs that don’t quite bring in enough money consistently, or unemployed people actively looking for work. But among the most important portions of this second group are those “not in the labor force.” This group has grown substantially in the past two decades, driving down the labor force participation rate to something like sixty percent.8 So how is this forty-or-so percent of the working-age population surviving? The retirement of baby boomers is a partial explanation and, by the 2020s, retirees had come to compose the largest single share. But they accounted for only half of nonparticipants. And retirement simply cannot explain the similar rise in nonparticipation among those in “prime working age” (between 25 and 54 years old). By the late 2010s, just under half of those between 25 and 54 who were not in the labor force were caregivers of some sort, particularly for ill or elderly family members. That number has risen significantly in the 2020s. Around a third were on disability, which replaced welfare as the primary means of government support in the US in the 1980s and 1990s.9 Meanwhile, the share of students has actually been declining within the total nonparticipant population and, among those of prime working age, composed only eight percent of the total by the late 2010s.10 Aside from retirement funds, most of the income that these individuals live on is derived from the family, not social services (even for those on disability). Households with prime working age “nonparticipants” are also disproportionately represented within the poorest fifth of the income distribution.11

Third is a different type of shortfall, which we might think of as a lack of decent work. Now, of course, there’s no such thing as good work, because the entire wage system is just a hostage situation forcing you to live at the whim of the firm. But let’s think of “decent” work as work that allows you to pay rent or even a mortgage, support children and maybe even a partner, have access to healthcare, and have some savings. Not too wild, but also not the reality that most of us are living. Why is this? Well, it has to do with the exclusion of most of the population from the core, high-productivity sectors that act as the real engines of economic growth. As a result, we get a “dual labor market” dominated by service work, and in which these services are divided between a small minority of high wage jobs and a vast majority of low wage jobs, the latter often serving the former. Dual labor markets are also associated with influxes of migrants, since these are low-productivity sectors like food service, janitorial work, childcare, and even construction, where the wage bill composes a very large portion of total costs and therefore profitability essentially requires low wages.12 Among the manufacturing industries that can’t be so easily relocated, long hours, dangerous work, and extremely low wages are the norm, as are periodic scandals about workers being paid under minimum wage or children being forced to work in meatpacking plants.

There has of course been talk about “bringing back good jobs” from overseas. But this has had limited impact. Maybe the closest thing to a success story is the growth not of good jobs but of new, low-wage manufacturing occupations across the US South, often driven by inbound FDI from East Asian firms, which then generate sub-contracted employment at component suppliers. But these are hardly “decent” jobs. In fact, it was firms like this that were at the heart of the child labor scandals in the South a couple years ago, where children were working as many as 60 hours a week in Alabama auto component plants supplying nearby Hyundai and Kia factories.13 In general, the reality has been more of the same: growth in low-employment but higher-wage sectors with the presumption that this small handful of better-paid workers will then spend that income in local communities. So, for example, the engineers working at one of the two huge federally-subsidized battery plants being opened in the small town of Moses Lake, WA will spend their money at local grocery stores, buy local real estate, hire local nannies for their kids, pay into the local tax base, etc., thereby spawning some multiple of lower-wage service jobs through their aggregate spending. In economic geography we call this “indirect employment,” and this multiplier effect is an extremely important part of how local governments calculate the potential “value” of any given investment. But it’s also obviously not the kind of employment base that can provide decent jobs for everyone, because the high-wage, low-wage inequity is baked into the basic dynamic: the one engineer’s income cannot really be divided up into that many “living wage” payments for subsidiary services.

How much, if at all, did the war in Ukraine and the genocide in Gaza count in this election?

A: The genocide in Gaza was almost certainly important, possibly decisive. Even a modicum of acknowledgement on the part of Harris and the basic skeleton of a ceasefire plan would have likely won her the election simply by drawing in the youth vote. Based on survey data leading up to the election and interviews with young people conducted afterwards, it’s clear that Gaza played an enormous role in the drop-off of youth support for the Democrats despite not featuring as the “main concern” for most voters. The situation is, in fact, quite surreal on the face of it. This is a world-historic atrocity being committed in front of our eyes, conducted with our tax money, all meticulously documented. The majority of Americans have been consistently shown to disapprove of the Israeli military action (although the number was closer to 50/50 right at the start) and, among youth, it’s an overwhelming majority who disapprove. That majority of youth has conducted massive protests, calling for the US to join the bulk of the international community in sanctioning Israel. There is absolutely no ambiguity about this situation. And yet the liberal consensus has been precisely the opposite: that any criticism of the genocide constitutes “anti-Semitism,” that Israel is entirely justified, and that there is simply no question about whether US tax money will continue to be used to massacre civilians and aid workers. By contrast, the Ukraine war was not particularly important to the election—though perhaps the Trump vote got a slight boost over concerns about the cost—but you can see the same frightening logic at play. It’s no surprise, but it’s certainly terrifying to see all the “level-headed liberal” types turn to bloodthirsty warhawks overnight.

Global context

Some speak of de-globalization, others of decoupling, what do capitalist value chains tell us?

As mentioned above, there is no evidence whatsoever of “deglobalization” or of any substantial “decoupling” of the US and Chinese economies. But there has been a relative stagnation in trade growth in both China and the US and, in particular, between the two. So the polarity of planetary production that formed in the era of globalization has, in fact, begun to break down, trade between non-wealthy countries has increased, and supply chains have grown more regionalized even while capital (visible in the movement of investment, the use of the dollar as a trade currency, etc.) remains entirely global and very much still dominated by US firms. We might say that regional trade and production linkages have grown more dense, that both are distributed between a proliferating number of nodes, and the long global links between these regions have been trimmed and even rerouted to a certain extent. But these production networks continue to operate on the same basic substrate: US dollars and capital from the lead firms based in the wealthiest countries. At the same time, however, within the lower-value segments of global trade, Chinese manufactures have become even more dominant, as have Brazilian agro-products and (now illicitly-traded) Russian oil and gas.

How does the war fit into this picture?

Well, the first question is: which war? Perhaps the most notable feature of the moment is the increase in armed conflict throughout the world, including at the very edge of Europe. Though none of these conflicts are yet “major” wars, they are no longer small, either. Nor are they the extended, decades-long counter-insurgency campaigns and slow-burn forms of civil strife that had been growing in frequency over the past few decades. They are instead genuine regional wars that have, since 2020, involved at least three of the ten largest militaries (as measured by sheer number of active members) in the world: those of Russia, Ukraine, and Ethiopia. The largest number of military casualties has, so far, been in the Russo-Ukrainian war, while the largest number of civilian casualties has been in the Tigray war. In both cases, these wars each individually saw more killed in their first two years than the total number of casualties in Iraq over the course of two whole decades, including during the initial American invasion. Meanwhile, the civil war in Sudan—which has its roots in the suppression of the Sudanese Revolution and has now evolved into proxy war (involving countries like the UAE, Saudia Arabia, and Egypt) for control over flows of gold at the headwaters of global supply chains—has now seen some three million people flee the country and eight and a half million become internally displaced. Altogether, that accounts for nearly a third of the country’s total population. And, although the total numbers from Gaza are much lower than those elsewhere, the character of the ongoing genocide is of course the most atrocious of them all.

All of this is certainly related, at least distantly, to the fracturing of global value chains. For example, the rightwing government in Poland, which has seen the largest increases in military spending in the world in recent years, is now positioning itself as the “savior of Europe.” Not coincidentally, Poland has also seen some of the fastest trade growth in the same time period, as Eastern European production networks have become central sites for (largely German) lead firms diversifying away from direct investments in China. Similarly, in the midst of its genocide, the Israeli government gestures toward a future Israeli-Indian trade corridor that would offer an alternate route to the Pacific. But it’s also important not to be too mechanical. While we can link large structural economic trends such as slowing growth rates, fragmenting trade, and the rise of certain peripheral economic powers to the general increase in conflict, it rarely makes sense to ascribe simple economic causes to any single war. Similarly, even though Gaza seems to compress the logic of our social system—and the abjection of the proletarian condition more generally—into a concise calligraphy of violence, placing too much weight on loose analogies poses the risk of equating excess with necessity, as if the specific configuration of social forces in a particular historical moment is merely the pre-determined expression of the underlying structural forces that caused it. In fact, the opposite is true: the contradictions immanent to capitalist production generate an inherent turbulence in the system that, exceeding a certain intensity, will generate a self-reinforcing chaos irreducible to its initial cause. It’s ultimately not really correct, then, to say that the genocide in Gaza is “caused” by some sort of underlying political-economic trend even if it might be “conditioned” or even “enabled” by these forces. The atrocity itself is quite clearly caused, in the immediate sense, by the virulently racist Israeli nationalists who worked for decades to craft the conditions in which a genocide would become possible and are now in the process of systematically conducting the genocide that they planned.

At the large scale, whether considering outright conflict or growing supply chain competition, are we “simply” talking about hegemonic change?

The idea that we’re in an “interregnum” between US and Chinese hegemony is itself an ideological image cast up by the operation of US imperial power itself, which is then used to bolster this power.14 If you look at the entire history of US hegemony, from WWII onward, almost every single decade has been marked by predictions of imminent decline, supposedly evidenced by the ascent of new challengers in Asia. In the early Cold War, it was the threat of a technologically advanced Soviet Union that had launched the both the first satellite and the first human being into space. A few decades later, the enemy was Japan, which had enjoyed some of the fastest rates of economic growth seen anywhere in the world up until that point. And then, of course, came China. In each case, the predictions not only proved wrong but were also deployed to reassert US interests throughout the globe. This argument was used to raise money for proxy wars and outright nuclear armament in the Cold War, to implement harsh tariffs against Japan and, ultimately, force through a monetary deal (the Plaza Accord) that triggered a deep economic depression lasting decades. Today, the same narrative is being used by American warmongers hoping to eat away at China’s meager advances, trigger an even more devastating political-economic collapse across the Pacific, and turn the Taiwan Strait red with blood.

Maybe more importantly, when we look at the actual historical process of hegemonic transition under capitalism—of which we have basically one, maybe two legitimate examples—there are a few things that stand out: First, the process seems to require an extended period of “major” warfare to be completed, in which the apparent successors of the leading power can rapidly shift. Few remember today, for example, that Germany was once considered to have a lead on the US in its competition with the British Empire because it sat at the forefront of global industrial innovation. Second, hegemonic transitions have never actually been simple head-on conflicts. Instead, the hegemonic power of certain loosely national fractions of capital and the government institutions that serve them has always been embodied in control over finance, over the currency of global trade, and over a dominant world military, and these factors have changed hands as much through cooperation as through outright conflict. Hegemonic shifts have been, up until now, basically agglomerative dynamics, in which new cores of capital that formed with the help of the older cores ultimately come to displace those old cores at first gradually and then rapidly in some sequence of crisis and war. But, more often than not, old and new find themselves allied in many of these major conflicts, even while they may be industrial competitors in other respects.15 Third, each shift in hegemony has also been a shift in geographic scale, meaning that any future hegemon would have to take on a more or less global form of governance for which no model currently exists.

At the same time, it’s also obvious that some sort of shift is occurring and that it has something to do with Asia. So, what’s really going on? And why does our moment both appear to signal a shift in hegemony and, at the same time, appear to fall short? Changes in the basic geography of global production help to answer this question. The cost discipline of the market has, since the postwar period, stimulated a nearly continuous relocation of industrial capacity westward across the Pacific Rim, forming new industrial territories in the littoral regions of East Asia in a sequence of developmental booms. These were accompanied by the rapid build-out of petroleum infrastructure in the Gulf States, the selective rehabilitation of Europe, and the military-industrial construction of the Israeli settler state, all under the auspices of US power. In each case, this has involved, first, an uneasy sharing of power among lead firms in the “condominium of states” that lie at the top of the imperial hierarchy and, second, the increasing delegation of power down to their subcontractors, located in countries further down that hierarchy. While lead firms have continued to enjoy a high degree of monopsony power even after outsourcing an enormous portion of their production in this fashion, the outsourcing process itself has ultimately produced new, monopoly-scale manufacturers that can then grow into lead firms in and of themselves.

As a result, new national and sectoral fractions of capital take shape and prove more capable of securing a greater share of the total profits flowing through these value chains.16 But this only takes place through a process that is simultaneously competitive and cooperative. The relationship with lead firms and the blocs of capital in the wealthy countries that helm them is, for the most part, one of unequal interdependence in which the poorer firms rely on the wealthier ones for crucial contracts. But this cooperation is also a method of enforcing cost-discipline on subcontractors, such that most of the competitive pressure is concentrated lower in the supply chain rather than directed at lead firms. So, for all the talk about a trade war between the US and China, which doesn’t really exist in most product lines, there has instead been a quite intense trade war lower in the supply chain between firms from mainland China and firms from Taiwan or South Korea, for example. Or, even earlier, we can point to how rising competition from China completely wiped out the “Southeast Asian Miracle” that had been occurring in the 1980s and 1990s, stunting the recovery from the Asian Financial Crisis in countries like Thailand and Malaysia and helping ensure that they would get stuck in the so-called “middle-income trap.”

Basically, hyper-competitive conditions are stimulated within the nucleus of the global manufacturing system, where a large number of initially very small firms are forced to operate on razor-thin margins. Most die out. Meanwhile, the most capable among them find that the only way to survive is to roll out rapid organizational, technological, and spatial “fixes” to these problems of profitability. So, they begin aggressive mergers and acquisitions that restructure their corporate organization, they figure out ways to mechanize assembly work and pour whatever money they can into R&D, and they begin relocating both to cheaper sites of production and to wealthier areas where they can acquire more advanced production techniques and serve higher-value markets with larger margins. As a result, they are then able to produce even more goods within their product line per unit of labor, thus worsening overcapacity across the sector as a whole and further lowering sectoral profit rates (even if they themselves profit from this). The end result is that the “global glut of manufactures” grows, creating more pressure up and down the chain to cut costs further. At the same time, though, the individual firm that has proved successful grows into a substantial conglomerate with its own monopoly powers.17

But at the same time, these companies still ultimately rely on contracts from lead firms above them. In fact, individual contracts (say, the contract to produce airpods for Apple) can compose a huge chunk of their annual revenue. Beyond a certain size, they’re in a better position to negotiate better deals on these contracts and take on more work that is more valuable, but they are still, ultimately, subordinate. It is this dynamic that produces the seemingly paradoxical situation that we see, in which more and more power over production has clearly been delegated to new cores of capital in Asia and yet accumulation is still clearly governed by lead firms in the wealthy countries. But this is a lopsided situation that can’t hold for long, and similar conditions have, in fact, prevailed prior to previous hegemonic shifts. Ultimately, though, hegemony is not really a “national” affair. Shifts in hegemony are more about changes in governance over the global geography of production and in the basic military-financial substrate that underlies it. And that’s precisely where we see no evidence of a major hegemonic shift occurring, at least not in the next few decades. For example: despite overblown reporting to the contrary, there have been no substantial moves to abandon the dollar; the control of major US financial firms, now epitomized by JP Morgan-Chase and massive asset management companies like BlackRock and Vanguard, has actually grown more expansive; and, despite rapid military growth elsewhere, the US remains the preeminent military power. And yet, all of these financial and military powers also operate increasingly through dangerous forms of delegation, as the rapid militarization led by rightwing forces in places like Ukraine and Poland suggests.

So this is not simply a matter of a “declining” US and an “ascendant” China?

No, not at all. In fact, that whole narrative is mostly just a distraction from the far more dangerous dynamics at play. Many of the key features of the “US vs. China” story are themselves either hyperbolic or outright falsifications. This is especially true of reporting on “China in Africa,” which I’ve discussed elsewhere.18 China is still a fairly poor country, on average. It has really not been engaged in the sort of head-on competition with core US firms that Japan, for example, became known for in the 1970s and 1980s. It’s certainly likely that China will get there soon. But, for now, most of these “trade war” measures are really less about warding off direct competition than about “punching down” to prevent Chinese firms from getting to the point where they might compete with important Western companies in the near future. And yet the past decade or so of anti-China policies have also had the effect of stimulating industries elsewhere in Asia, as well as in Eastern Europe and Mexico, more than reviving production in the US. Insofar as there has been any increase in industry, many of the largest new investments in manufacturing have been funded by South Korean, Taiwanese, Japanese, and German firms. So, what we’re seeing is that, despite the half-assed attempts to lock China out of the game, all this delegation of power over production is nonetheless still generating subordinate cores of capital across Eurasia that are growing more powerful and taking on an increasing number of “sub-imperial” functions at the mezzanine levels of the imperial order.

And this creates the conflicts we were talking about before. But these conflicts, quite notably, do not involve China (though of course they have some business ties), and rarely even directly involve the US anymore—at least no in the “boots on the ground” sense of the Bush years. Of course, the US is still usually offering financing, some training, peripheral drone strikes, and of course the ever-present positioning of aircraft carriers in the background when it feels that the conflict might threaten global trade. In the place of classic war on terror interventionism on the part of the imperial hegemon or even the older Cold War proxy politics between “superpowers,” we instead find the most active involvement among sub-imperial powers themselves, operating largely in their own interests. Some of these are powers in decline or under threat, such as the Russians and the French, and others are clearly on the ascent, such as the Emiratis, the Saudis, the Turks, and of course an increasingly far-right administration in India. Take the Sahel as a case study. The US has, of course, been expanding its presence in subtle ways, such as via AFRICOM and its network of subservient military partners like Kenya. It does drone strikes and trainings and pads the pockets of certain elites. And yet much of this is relatively passive, compared to the active interventions by the French—who have deployed legionnaires across the desert to secure Uranium deposits—and by Russian military firms like Wagner, who are now in conflict with similar mercenary groups from Ukraine deployed to challenge Russian interests in North Africa.

The same is true in the economic domain. For example, you’ll hear a lot about China trying to acquire ports across Africa to gain key logistical chokeholds and to station its military. But when you dig into the facts on the ground you find almost no evidence of this aside from the single base in Djibouti (which exists alongside bases associated with a number of other countries), the subcontracting of some port construction work to Chinese companies, and a few container terminals that are managed by Chinese firms—the latter are often erroneously referred to as evidence of “Chinese-owned” ports. Obviously, China is a huge economy, and Chinese firms are the most important international construction and engineering contractors out there. They are particularly prominent in the African market and do, in fact, hold a majority of the market share in large construction projects on the continent. But construction firms don’t own the things they build. The mere presence of Chinese construction companies in Africa is a very different thing than outright financing, investment, and ownership, all of which operate through much more complex chains of capital most often routed through traditional multilateral institutions like the IMF and World Bank.

By contrast, Turkish firms and military interests have been engaged in exactly the sort of activities that China is criticized for, and yet this barely appears in the media. Turkish companies have signed major port management deals (not just terminal leasing) across the continent and have been consistently accused of engaging in corrupt business practices afterwards, including the illicit funneling of untaxed cash back to Turkey. The most egregious case is Somalia, where Turkish firms have long-term contracts to manage both the seaport (Albayrak Group) and airport (Favori LLC) in Mogadishu, as well as ports further north and offshore oil prospecting rights (alongside the US). These deals were negotiated with the direct assistance of the Erdoğan administration, following from a series of aid agreements. Moreover, after a series of military deals were signed, Turkey opened a massive military base in Mogadishu, where they train the Somali national armed forces (and facilitate sales of Turkish weapons to the country). The most recent of these deals will soon allow the Turkish navy to patrol Somali waters, serving as the country’s de facto navy and coast guard, while also signing over at least a third of the revenue from Somalia’s offshore exclusive economic zone to Turkish companies.19 Nor is Turkey alone. For example, capitalist interests from the UAE have been literally plundering Africa, illicitly funneling massive amounts of gold out of the “artisanal” mining industry, which is then laundered in the UAE before making its way to other financial centers like Switzerland or Hong Kong.20 To these ends, the Emirati government has been financing one faction (Hemeti and his Rapid Support Forces, or RSF) in the Sudanese Civil War and therefore bears a major responsibility for the ongoing refugee crisis. In fact, it is even more complicated than this, since many of these RSF soldiers received their combat experience in Yemen, where they fought another proxy conflict on behalf of the UAE.21

So, overall, what is the picture? It’s one where the delegation of power within the global imperial hierarchy also transmits tension downward, stimulating intensive competition in the middle layers of the value chain and triggering outright conflict at the global headwaters of value. Meanwhile, the upper echelons of the chain have continued to appropriate enormous masses of profit, even if the growth of other cores of capital has made their share of overall flows shrink. But the delegation of power is also risky, because it poses the prospect of disruption due to either intra-class conflict between fractions of capital or inter-class conflict, as workers at increasingly large contract manufacturers find themselves more able to mobilize industrial actions to demand higher wages.22 So, rather than hegemonic transition from the US to China, we see a particular method of bolstering US power that also encourages the rise of this very large, very diversified field of pan-Asian capital which in some respects operates like a single “bloc” but, in most cases, exhibits extremely divergent and often conflictual interests that play out in both the economic and geopolitical sphere, with often violent consequences. After the fall of the Soviet Union and the defeat of the Japanese in the trade war, the dependency theorist Samir Amin warned of an imminent “empire of Chaos,” in which desperate attempts to bolster a decaying hegemony occur in the absence of any new hegemonic contender. And that seems to best describe the conditions today. There is simply no core of accumulation out there that seems capable of supplanting the hegemony of the US, despite this hegemony hollowing out as more power over production is delegated abroad.

Militancy

In Italy, militancy is mainly concentrated in large university cities, which, however, demographically, socially and culturally are minoritarian. Some collectives are beginning to ask how to intervene within different contexts, have you wondered what might be useful paths in this regard? Or should we hope for an autonomous development of militancy in these contexts?

This condition is common not just in Italy but across many countries. At the same time, we also have a tendency to read this problem in registers drawn from the past, treating it much the same way that the New Left did sixty or so years ago. But a lot of things have also changed in that time. For example, you say that large university cities are the minority and, while I understand what you mean, the largest universities are generally in the largest cities, and today they are also often among the largest employers in those cities. And, compared to fifty years ago, many of these jobs are low-wage, high-demand positions. I’m not sure what the conditions of work are in Italy, but in the US, for example, the bulk of university classes today are taught by adjuncts or grad students being paid less than your average factory worker. Meanwhile, universities today are vast real estate schemes that help to anchor local property markets. They also serve as sites of advanced R&D for military-industrial interests. If a militant strike among academic workers shuts down the premiere research university in a given city, this will therefore have a substantial economic impact. Moreover, as higher education has generalized across the population, more students today come from lower-class backgrounds. More are therefore working low-wage jobs outside the university, commuting back to working-class neighborhoods, and of course suffering under immense debt. So these are, in every way, major sites of class conflict in and of themselves. We have to abandon that old idea from the New Left that these are “bourgeois” strata or even “professionals” that somehow aren’t part of the larger proletarian class and therefore need to enter into that class from outside. In all but the most elite institutions, that simply is no longer true.

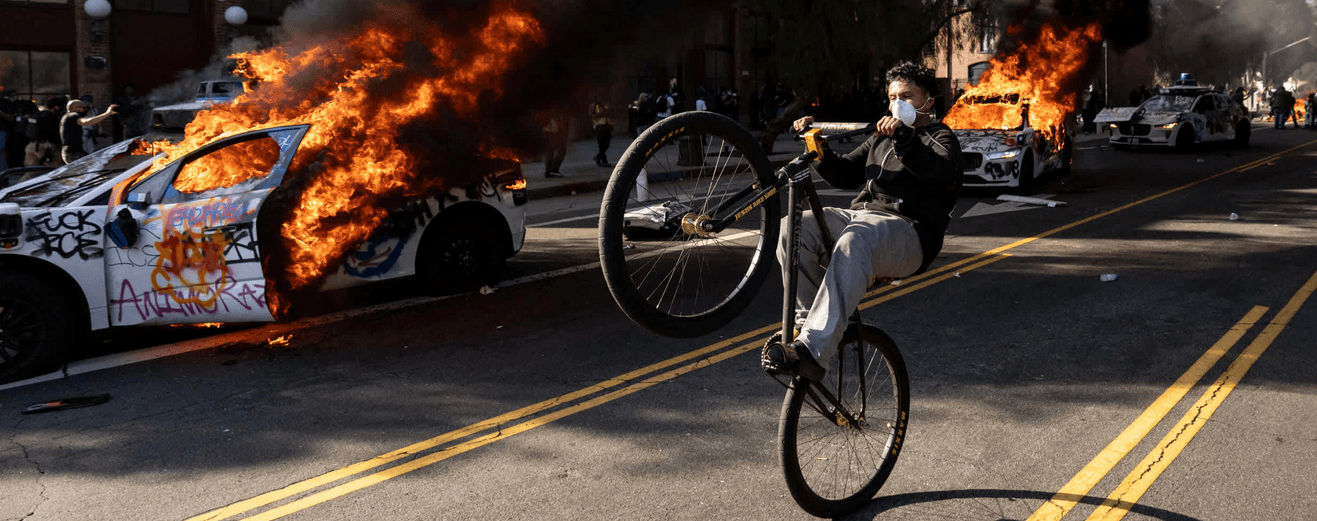

But there is always a problem of insularity, whether you’re talking about the university versus society, different industrial sectors, or even different occupations within the same sector. Most class organizing emerges first in the form of specific subsistence struggles, which focus on the immediate terms of survival: how much are you getting paid, how much does your rent cost, is your job likely to kill you, are the police likely to kill you, etc. But these issues are also often contradictory, since they are simultaneously specific (i.e., this group of workers making specific wage demands relative to this workplace) and also general, resonating with larger segments of the class (i.e., everyone’s wages are too low). On top of this, struggles tend to trigger larger conflicts that then take on added meanings and gain their own momentum, becoming important expressions of class conflict in and of themselves—and thereby completely exceeding their initial subsistence concerns. We see these contradictions then play out in tactical tensions. Take, for example, the recurrent riots against police killings. Initially, these have a very clear focus: the killing of a specific individual by specific police officers. Some therefore interpret the “meaning” of the uprising in an equally specific way, calling for those individual officers to be punished. Others interpret the uprising in a more general way, but still limited by this basic logic of subsistence demands, calling for widespread reforms of the criminal justice system, more oversight, to hold all police legally accountable for their murders, etc. But once the event generalizes into an uprising, even this wider interpretation doesn’t quite capture its actual political import, because it doesn’t grasp all the additional meanings taken on by the momentum of the uprising itself—which of course tends to become a more general rebellion against conditions of life in capitalism across multiple registers.

This excess that is the most important aspect, because it is only through this syncretic, self-referential dimension that any given struggle can jump beyond its initial limits.23 And this is also the opening for organization, which helps to elaborate the struggle by bridging the insularity of these many individual subsistence demands. There are plenty of historical examples of how this has been done in the past. But it’s a fundamentally practical question, which means that it’s very sensitive to the local problems you are facing. You can’t just transplant these models from history into the present because they were inseparable from their environment. If you try, you end up with a dead, empty husk: the various sects that think of themselves as “parties” and “unions” today, for example. Meanwhile, basic structural shifts in employment and geodemographics have obviously changed the coordinates such that it no longer makes sense to try to build a peasant army today, for example, even if the historic experience of revolutionary organizing among peasants still offers useful lessons. So, we really have to respond to your core question by breaking it down and sharpening it into a series of more pointed ones: what exactly are these collectives who hope to escape the university trying to do, and where are they attempting to go? Similarly, what do they conceive of as “militancy” and how is it measured? And, on top of this, we’d then need to understand more of the specific social conditions involved. Obviously, it helps to build breadth beyond one’s immediate surroundings. But there’s also a tendency to disregard our own experiences of class and the various subsistence struggles that we face day-to-day, imagining that the “real” struggle is located elsewhere, among some special demographic that is somehow closer to a pure proletarian condition. People then attempt to self-flagellate, denying their own existence and instead seeking out this “pure” experience of class or playacting at a more fanciful image of “militancy.” In reality, we all experience different aspects of proletarian existence. We can fight against it from multiple positions, so long as, in the process, we are also exceeding those positions.

You often say that what we will see, in terms of class organization, will be something totally different from what we have seen so far. It will not be “dual power,” autonomy, the classic Marxist Leninist party, etc., etc. Do you feel like delving a little deeper?

Q: I argue that class organization will not adopt the exact names that it has taken in the past, not necessarily that it won’t take similar forms. This approach is just a way of trying to force people out of their obsessive, melancholic attachment to leftist history. The first thing you have to do if you’re trying to organize is obviously just to look at the conditions surrounding you as they are, not how they were a hundred years ago. At the practical level, though, I don’t think future organization will be something “totally different from what we have seen.” In fact, I’d say my position is exactly the opposite: we don’t need some magical “new” form of organization, we need to return to much older principles of partisanship which, of course, helped to inspire all of these examples you list. You can’t just transplant these historic examples wholesale, but you can “regenerate” partisan organization in forms that can thrive within the present ecosystem. Ultimately, this is what the theory of the party is all about and I’m a huge advocate of the party, in the orthodox sense. In fact, whenever you’re talking about organization, or at least organization with some sort of orientation toward a political horizon, you are talking about parties, whether you know it or not. But the problem is that today people hear “orthodox,” and “party,” and they instead think I’m talking about the sort of dogmatic, crepuscular entities produced by the death throes of the global Communist Party defeated last century. Or even worse, their political education has been so stunted that they think “party” refers to an electoral entity!

Today, we obviously find ourselves in a doldrums, surrounded by increasingly common and increasingly sizable uprisings of various sorts, but also unable to adequately engage with or even understand these events, which remain largely nihilistic and apolitical or, at best, express a sort of radical republican sentiment. We are therefore left with vague theoretical platitudes and the rudimentary forms of organization that arise in the immediate situation of the revolt. And, although these makeshift measures then get romanticized or critiqued in the aftermath, they aren’t really chosen as a conscious strategy. They’re the result of practical questions colliding with the commonsense ideology of the era. So, the limits of organization that arise are in fact symptoms of something deeper, operating first at the structural level—i.e. the forces producing our immediate environments and therefore posing to us the particular practical concerns that arise in a revolt—and only second at the level of intentional political tactics. Since propagandistic interventions arguing that people should do something else only operate at this secondary level, their impact is extremely limited. For example, in all the uprisings of the past fifteen years, you had plenty of participants (in fact, often people in very decisive roles) urging people to adopt more rigorous forms of organization, advocating for a “worker’s party” or something like that, and plenty of people out trying to sell their own little sects. But no one was buying.

And that’s because the whole “marketplace of ideas” model where we go and “communicate” our politics and try to get people to agree with us is ass-backwards. This is the problem with all those people who think the failure of the uprisings of the 2010s was that they chose to adhere to principles of “horizontalism” and “leaderlessness.” No one chose this, of course, and plenty of people were there arguing for the opposite—and, in fact, the “worker’s party” was tried in Greece (SYRIZA), in Spain (Podemos), in the US (Sanders), and in the UK (Corbyn), and it systematically failed as well, for remarkably similar reasons. Ultimately, the point is that political ideas aren’t adopted through skillful argumentation. They’re inscribed into us in our physical life. You can argue all day with someone that the police aren’t “part of the 99%” and no matter how reasonable you are, how much evidence you offer, they will still not believe you. But if they go out and get bonked on the head just once by a police baton, they are suddenly a convert. It is, quite literally, a political baptism—with all the religious shock that this entails. Ideas don’t enter the mind through the ears, they enter through open wounds, through joints burning after endless shifts of dead-end jobs, through feet blistered by long days on the picket line, through hands torn open by some machine, arms coated in grease scars, the lining of lungs filled with teargas. One consequence of this is that, insofar as we “communicate” our political ideas, we do so largely through action in the moment of the revolt.

So, if you want to advocate for one particular type of organization or strategic orientation, you have to take a tactical lead in the uprising, whatever it is: perform concrete acts that surpass the immediate limits constraining the extension and elaboration of the political sequence. In some cases, the organizational form that you are arguing for in the abstract may even serve this practical function. But, in many cases, it actually has little to do with whatever larger-scale theory of organization you have, since the action is maybe nothing more than hauling in food for people, breaking in to occupy the fulfillment center rather than picketing out front, smashing the first window of parliament, or of course setting the first police station ablaze. Whatever it is, though, it should be facing outward, rather than focused on critiquing or attacking or arguing with other participants. You’d think that the hyper-sectarianism of the New Left would be enough of a cautionary tale, reminding us that we have to be kind to one another, and ecumenical. But it’s difficult, because these actions are also a gamble. Leading acts are always dangerous ones and it’s never clear if they’ll have the intended effect or if they’ll turn out to be adventurist oversteps. Someone will always disagree with you, terrified that you are endangering everyone involved.24 If you succeed, though, other participants will be magnetized to the sigils of your politics and thereby opened to the ideas that attend these sigils. These practical arenas are the starting point of organization, from which we begin to aggregate a sort of collective consciousness of how to elaborate struggles beyond their initial limits. But to start, there is only one suggestion: take the lead, don’t just talk about it.

NOTES

- Mike Davis, “Trench Warfare: Notes on the 2020 Election”, New Left Review, 126, Nov/Dec 2020. <https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii126/articles/mike-davis-trench-warfare> ↩︎

- Alexander Sammon, “Want to Star Into the Republican Soul in 2023?” Slate, 30 May 2023. <https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2023/05/rich-republicans-party-car-dealers-2024-desantis.html> ↩︎

- National Low Income Housing Coalition, “New Census Data Reveal Voter Turnout Disparities in 2022 Midterm Elections”, National Low Income Housing Coalition, 15 May 2023. <https://nlihc.org/resource/new-census-data-reveal-voter-turnout-disparities-2022-midterm-elections> ↩︎

- Eva Xiao, Clara Murray, Jonathan Vincent, John Burn-Murdoch, and Joel Suss, “Poorer voters flocked to Trump – and other data points from the election”, Financial Times, 09 November 2024. <https://www.ft.com/content/6de668c7-64e9-4196-b2c5-9ceca966fe3f> ↩︎

- For an overview of the issue of measurement, see: Adam Tooze, “Chartbook 327 From ‘anti-core’ to ‘felt inflation’: Or how I calmed my populist demons & resolved my cognitive dissonance on inflation, and how the Fed could do more to help”, Chartbook, 16 October 2024. <https://adamtooze.substack.com/p/chartbook-327-from-anti-core-to-felt> ↩︎

- For more detail, see the full article: Neel, Phil A., “The Knife at Your Throat”, The Brooklyn Rail, October 2022. <https://brooklynrail.org/2022/10/field-notes/The-Knife-At-Your-Throat/> ↩︎

- Overall, EVs require fewer parts and have simpler powertrain designs, therefore representing the further rationalization of an already highly rationalized industry that today employs much fewer workers (in absolute terms, per unit of output, and per capita) than it did in, say, its postwar peak, when nearly a sixth of the US workforce was employed directly or indirectly by the auto industry. ↩︎

- For context, the last time the figure was that low was in the 1970s, when women had only just begun entering the workforce en masse. ↩︎

- On the rise in disability, see: Chan Joffe-Walt, “Unfit for Work: The startling rise of disability in America”, NPR, 22 March 2013. <https://apps.npr.org/unfit-for-work/> ↩︎

- Women entering the workforce was the primary reason why the labor participation rate began to rise in the 1970s, but there has been no significant “return to the household” driving the current trend. The basic reasons given for nonparticipation didn’t differ by gender. That said, most female nonparticipants who were not retirees lived with a spouse or partner and women with less than a high school education still compose the largest prime working age group outside the labor force. Meanwhile, men outside the labor force most often reported living with a parent. ↩︎

- The data on the labor participation rate comes from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The data on the composition of the non-participant population comes from a 2017 research paper on the topic by the Hamilton Project: Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, Lauren Bauer, Ryan Nunn, Megan Mumford, “Who is out of the labor force?” The Hamilton Project, 17 August 2017. <https://www.hamiltonproject.org/publication/paper/who-is-out-of-the-labor-force/>. More recent data on the breakdown of the total non-participant population, including those 55 and older, is summarized here: Victoria Gregory, Joel Steinberg, “Why are Worker’s Staying Out of the U.S. Labor Force?”, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 02 February 2022. <https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/regional-economist/2022/feb/why-workers-staying-out-us-labor-force> ↩︎

- The classic study of the phenomenon is: Michael J. Piore, Birds of Passage: Migrant Labor and Industrial Societies, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979. ↩︎

- Mica Rosenberg, Kristina Cooke, and Joshua Schneyer, “Child workers found throughout Hyundai-Kia supply chain in Alabama”, Reuters, 16 December 2022. <https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/usa-immigration-hyundai/> ↩︎

- My next book, hopefully out sometime next year, talks about the issue of hegemony in detail. This section of the interview is a very brief summary of some of its core arguments. ↩︎

- Thus, the British became the preeminent naval and, later, financial power in part through their close links with the Dutch in the wake of the Glorious Revolution, and the Americans played a similar role with regard to the British after the turn of the 20th century. ↩︎

- Ashok Kumar has documented the process in detail in: Monopsony Capitalism: Power and Production in the Twilight of the Sweatshop Age, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020. ↩︎

- We’re beginning to see this, for example, with companies you’ve probably never heard of such as Luxshare Precision, Longcheer, Huaqin, or GoerTek, which were all very small suppliers for contract manufacturers like Foxconn, then began winning direct contracts from lead firms like Apple, and are now major manufacturers of “white label” goods—which are most of the cheaper smartphones and other electronics on the market, readymade by these companies using their own designs and purchased by a company which then just slaps its brand on them. Some may be on their way to becoming the next Foxconn. ↩︎

- See, for example, my interview with Turkish collective Komite: Phil Neel with Komite, “Hostile Brothers: New Territories of Value and Violence”, Brooklyn Rail, November 2023. <https://brooklynrail.org/2023/11/field-notes/Phil-Neel-with-Komite/> ↩︎

- Kiran Baez, “Turkey signed two major deals with Somalia. Will it be able to implement them?”, Atlantic Council, 18 June 2024. <https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/turkeysource/turkey-signed-two-major-deals-with-somalia-will-it-be-able-to-implement-them/> ↩︎

- For a detailed breakdown of the process, see: Marc Ummel and Yvan Schulz, “On the Trail of African Gold: Quantifying production and trade to combat illicit flows”, Swiss Aid, May 2024. <https://www.swissaid.ch/en/articles/on-the-trail-of-african-gold/> ↩︎

- Many young soldiers recruited into the RSF actually thought that they were applying to be guest workers in the wealthy Gulf States. Instead, they were shipped into a warzone and handed a gun. For more detail on these groups, see: Adam Benjam and Magdi el Gizouli, “Marketing War: An Interview with Magdi el Gizouli”, Phenomenal World, 30 September 2023. <https://www.phenomenalworld.org/interviews/magdi-el-gizouli/> ↩︎

- See: Ashok Kumar, “When Monopsony Power Wanes – Part Two: Subjective Agency”, Historical Materialism, 32(1), 2024. pp.3-33. ↩︎

- Classically, this is the movement from “economistic” forms of class organization to properly political forms of action, as discussed in Marx’s critique of English trade unionism and Lenin’s critique of economism. This is also the space in which a union becomes possible between the “historical” party of recurrent mass struggles within the class and the “formal” parties of intentionally self-organized fraction of the class and this union of historical party and many individual formal parties constitutes the “Communist Party,” as such—often captured by the notion of a broader “communist movement” or formalized as a specific “Communist International” that coordinates between the many formal parties. ↩︎

- But concerns with “safety” are also the seeds of a the snitch mindset. ↩︎

Ti è piaciuto questo articolo? Infoaut è un network indipendente che si basa sul lavoro volontario e militante di molte persone. Puoi darci una mano diffondendo i nostri articoli, approfondimenti e reportage ad un pubblico il più vasto possibile e supportarci iscrivendoti al nostro canale telegram, o seguendo le nostre pagine social di facebook, instagram e youtube.

american electionchinacrisisdecouplinginflationmilitancytrumpUsawar