From Tor Sapienza to San Siro: conflict breaks out in the Italian peripheries (Part I)

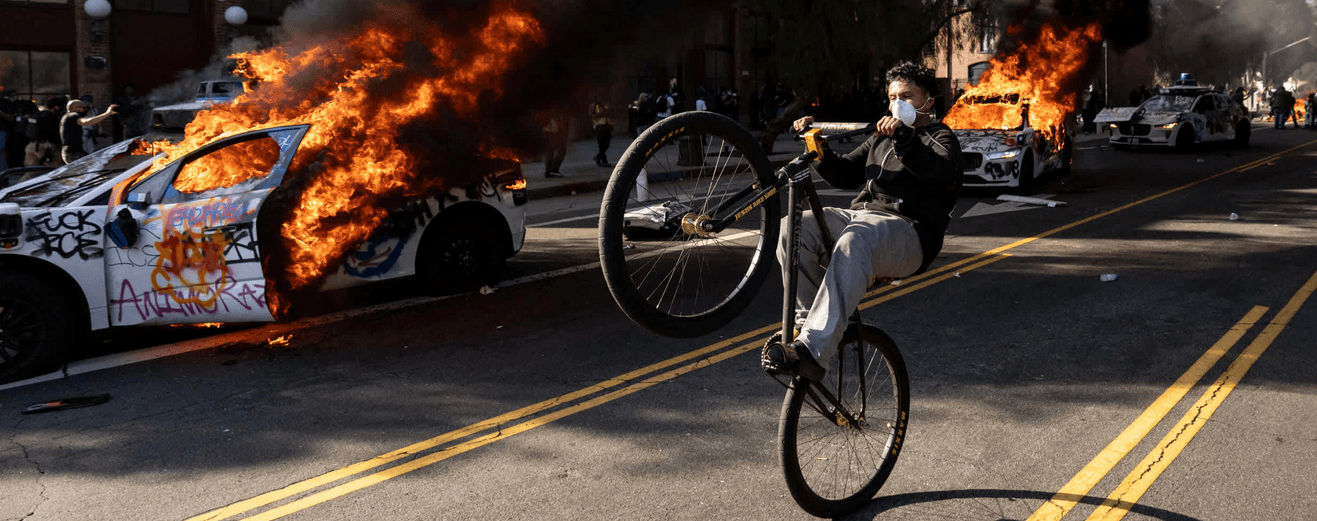

Two weeks ago in Tor Sapienza – a neglected, working-class neighborhood at the eastern borders of Rome – a migrant care center (Sistema di protezione per richiedenti asilo e rifugiati-SPRAR) was assaulted with clubs and firecrackers by enraged residents over a spate of thefts and an alleged rape attempt by a migrant. That center was set up from the previous city council headed by neofascist Alemanno mayor, in a neighborhood otherwise completely devoid of services – that was left abandoned in the past two years also by the centre-left administration of Marino (Democratic Party).

The protests were also participated by local committees against urban blight. These committees were set up by fascists trying to stage a comeback, after having been stopped by the autonomous movements and having lost their bankrollers in city and regional government in the past years. The fascists then formally disbanded, putting away their party flags, only to show up again in the square with their committees, holding Italian national flags. A strategy quite similar to the one promoted by the Golden Dawn party in some neighborhoods in Athens in order to gain popular consensus.

As many past events (most notably the “Pitchforks Revolts” in 2012 and 2013) featuring a “citizens’ uprising” apparently devoid of organized presence of autonomous movements, these events enjoyed a massive media overexposure – with liberal outlets (and also grassroots reformist ones) crying foul for the presence of fascists. Actually, the numbers of the latter were quite limited and their attempt to stage a “March of the Peripheries” along with other disgruntled citizens from the capitol’s outskirts ended in a complete failure, only managing to barely rally a thousand people.

Thus, thought the fascists’ attempts to exploit the plight of the citizens are not to be underestimated, one has to recognize the level of popular rage and discontent expressed by that composition, that not only overtly protested the institutional visit of the mayor Marino, days later after the events, but also the separate presence of other politicians, from Paola Taverna of the populist 5-star movement to Mario Borghezio of the xenophobic Northern League party. One can say that the “real” squares came back with a vengeance: after years of delusions about virtual agoras, the mayor chose a bar to meet the enraged residents of Tor Sapienza, and the struggling Roman movements for housing rights called for a neighborhood assembly in the local Piazza De Cupis; in order to discuss local issues, establish some sort of social mediation to address security concerns and build a solidarity network to stay in that context after the predictable, future withdrawal of the institutions.

Some lessons can be learned from the Tor Sapienza event. The first one is that, in order to prevent social discontent to fuel a race to the bottom against migrants, it is important to part from a welfare-dependency rationale. Differently from the CIEs, veritable concentration and internment camps for migrants both in their architecture and procedures (and secluding them from the outer society), the SPRAR system offers a more “acceptable” way for liberals and reformist left-wingers to manage immigration flows, as it keeps them in touch with the local community, gives them a shelter and (very small) allowances and involves associations and charities to provide them with assistance, education and more. Still, though a number of comrades and good-willed people may work in such places (some of the workers of the SPRAR center reportedly called housing rights activists for protection during the Tor Sapienza events), the SPRAR system actually fuels a do-gooder, welfare economy which is largely – if not entirely – supportive of and dependent on capitalist reproduction and its governance of migrations; prevents migrants from self-organizing themselves in order to reclaim their rights; and generates social hatred, fanned by the spreading of urban myths about “foreigners being given a daily allowance of 40€ in front of impoverished Italian blue-collars being sacked and losing their houses”.

Also, many of the Tor Sapienza residents that participated in the assault expressly claimed not to be racist. And actually, except for the fascist parties and movements and their sympathizers, the racist character in these events (and more in general throughout Italy) is mainly driven by economic reasons: namely, migrants becoming competitors for an increasingly shrinking share of jobs, welfare, social housing and services. Thus, in order to break the complementary rationale of institutional racism (which endorses migrants not as human beings but as a “reserve army of labor” in Marxist terms) and right-winger, neo-colonialist one (let’s close our borders and “help” them to develop their countries) it is important to reaffirm the connection between antiracism, antifascism and anticapitalism. And to build grassroots, bottom-up networks of solidarity, cooperation and counter-power in order to reclaim through struggle spaces and possibilities which have been abandoned by the State and Capital when deemed as unproductive.

To be continued…

Ti è piaciuto questo articolo? Infoaut è un network indipendente che si basa sul lavoro volontario e militante di molte persone. Puoi darci una mano diffondendo i nostri articoli, approfondimenti e reportage ad un pubblico il più vasto possibile e supportarci iscrivendoti al nostro canale telegram, o seguendo le nostre pagine social di facebook, instagram e youtube.