Regional Elections in Italy mark a stop for Renzi’s neoliberal project

About a voter out of two did not go to the polls for electing regional governors: this trend steadily consolidated through the years, with a net 10% average voters’ loss in comparison to previous elections (2010) and expresses a rising discontent about the Italian ruling class, and its forms of representation and cronyism. There are also other reasons, ranging from the growing expulsion of Italian citizens from welfare and public services’ to disillusion about the possibility of implement reforms undesired by the European institutions and specularly growing self-referential character of the Italian ones. Actually, this lack of legitimacy may already affect the future Senate that, accordingly to a reform bill under review, may be composed of regional and local council representatives. Renzi himself, too, was not directly elected by the people; rather he was appointed by the former President of Republic Napolitano after a majority in his favor came together in the Parliament.

The poor performance of the Democratic Party (PD), which gathered about 25% of the vote on a national scale, may spell the end of the “Party of the Nation” project: that is, gradually emptying the pale, leftish character of the PD itself in order to rebrand it as a post- and non-ideological natural party of government, attracting also rightwing votes. More worringly for the European institutions, the approval for their policies (which was already a political minority in 2013 – if one adds abstention to opposition – but a parliamentary majority thanks to the support of a – now crushed – moderate right to the PD) may not survive the next general elections, in case the Democratic Party retains the same outcome. Moreover, Renzi was not able to shape and consolidate a local ruling class loyal to him. His flagship candidates were beaten in the Veneto and Liguria regions, and elsewhere other candidates loyal to the old Democratic Party leadership, or with stronger connections to territorial vested interests and crime, were elected – thus undermining the effectiveness of Renzi’s charisma in a “personalist” party rethoric framework.

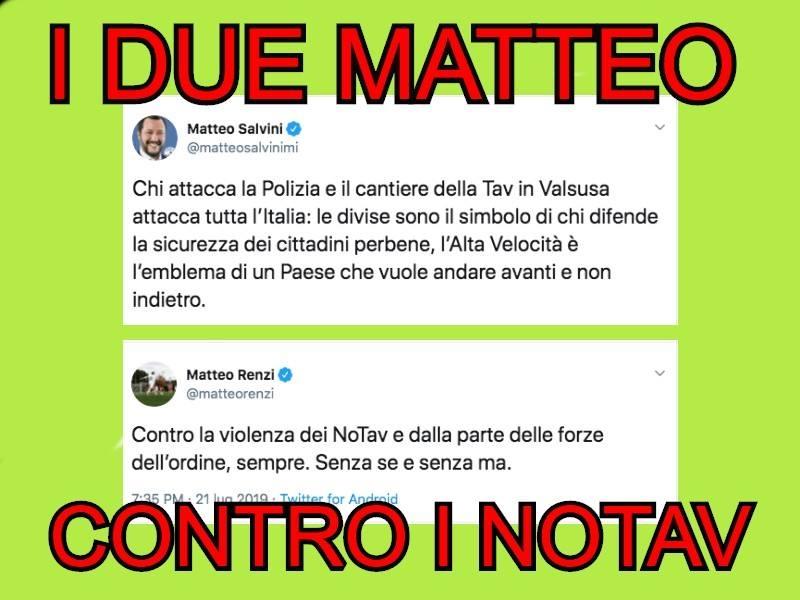

The xenophobic Northern League (Lega Nord) party, which featured candidates from the neofascist Casa Pound organization – that largely restyled itself under the “Sovranità” (Sovereignty) party brand – advanced in many regions, but utterly failed to attract consensus in southern Italy. That was in part because of the historical “southerner-shaming” by the Northern League leadership, but also thanks to the popular hostility organized by the autonomous movement against Salvini’s supporting rallies. Salvini cannot become yet a viable contender for Renzi because of the radicality of his positions and part of its political space occupied by attempts by former Berlusconi associates to set up a Cameron-esque Conservative party and by the Five Star Movement (see below). Yet, it remains worrisome how much his racist and covertly murderous discourse during the electoral campaign was tolerated, spreaded and translated into common sense by media and other parties.

The good result of the populist Five Star Movement, which came out as the second party almost everywhere, showed the ultimate failure of Renzi’s “government populism” politics to co-opt a large part of anti-system discontent. In spite of its evident contradictions, the Movement managed to attract both voters from the right (thanks to its utilitarian anti-migrant stance and skepticism about the euro) and from the left (gathering disgruntled PD supporters, mostly from the education sector, and featuring a basic income law proposal).

In this context, there cannot be such a thing as an Italian “Podemos”. The Coalition hypothesis suggested by the mainstream metalworkers’ union FIOM, some leftish social-democrat institutional parties, associations and a part of the social centres may look closer to an Italian Syriza: but without any real movement beyond itself, and with a more prominent attitude to institutional compromise and with its ideology rooted in fordist-age relations and practices.

Yet, political conditions exist for a bottom-up, grassroots autonomous movement to exploit this seminal crisis of the Renzi government, and address the social categories that were left behind by its process of dismantling of the leftist identity: teachers, pensioners and state employees. The housing struggle movement, too can retain its pivotal role of social opposition in the coming months, and a renewed attention will have to be addressed towards the “new poors” of a former middle class in shambles and the peripheries. Once again, the struggle has just began!

Ti è piaciuto questo articolo? Infoaut è un network indipendente che si basa sul lavoro volontario e militante di molte persone. Puoi darci una mano diffondendo i nostri articoli, approfondimenti e reportage ad un pubblico il più vasto possibile e supportarci iscrivendoti al nostro canale telegram, o seguendo le nostre pagine social di facebook, instagram e youtube.