The neo-ottoman project of Turkey underwent a serious crisis during the Gezi Resistance and is now facing another crisis. If Gezi was a sudden cardiac arrest in the heart of Islamic neoliberalism (which it never recovered from), the past weeks political crisis in the corridors of the élite has been a concussion of its brain.

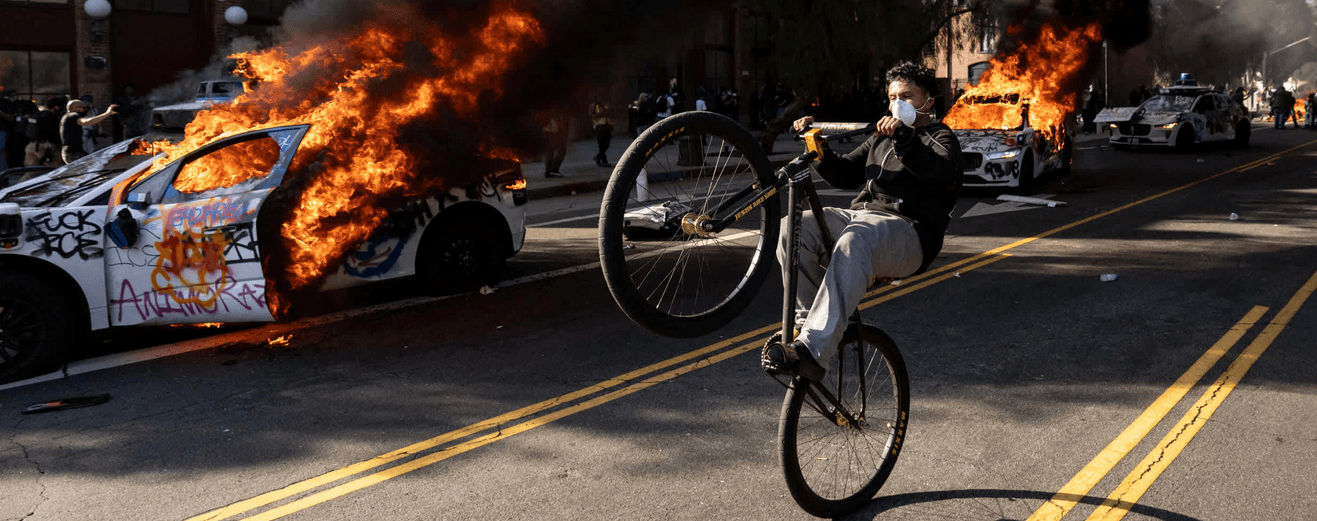

We remember how much Gezi, with the force of a enormous metropolitan strike in the city-factory, hurt the bosses. The revolt earlier this year provoked a falling stock market, made tourists choose other destinations while multinationals were boycotted and protests organized outside malls, shops and cafés that refused to help injured during the revolt or in some way chose the side of the city of neoliberal development instead of that of struggles. When, in acts of solidarity, thousands twice crossed the bridge from the Asian side to the European or when the barricades stopped the traffic in the central parts of town, it further added to the economic damages that have been estimated to billions of dollars.

The recent episode has caused much instability, just as its preceding injury. The Turkish Lira is hitting low records against the dollar and euro while the stock index continues falling as foreigners dump Turkish debt. “There’s panic, there’s no liquidity” said Arda Kocaman, the head of treasury at Finance Invest in Istanbul by e-mail. The economic crisis seems to lurk around the corner and economists are predicting a rise in unemployment alongside a lower economic growth. As a matter of fact, a 2014 recession doesn’t seem improbable at all. In any case, Turkey has definitely joined the lines of its global nations in the crisis of neoliberal governance.

Erdogan the Sultan and his court on one side and the Fethullah Gülen the Imam and his community on the other, previous allies and the recipe for AKP’s success, are now in open conflict. Erdogan, who was one of the most powerful men in the Middle East before the Gezi revolt is now perhaps in greater difficulties than ever after almost 11 years in power. The old best friends of the Sultan seem to be gone and he finds himself in the midst of a political crisis which he seems to confront with a gattopardian maneuver reshuffling his Cabinet in order to find an exit: “everything needs to change, so everything can stay the same.” (1)

The Gülen Community, in the view of many responding to Erdogan’s draft bill regarding the closing of prep schools and reading rooms (a great source of income for the Gülenists), has been attacking those businessmen and politicians in the nexus of the public and the private who benefitted from the AKP’s urban renewal and mass housing projects (TOKİ) – projects that were targeted by the Gezi revolt. In this way, the Gülen Community poses itself as the force bringing about the justice demanded by the social composition at the core of the Gezi resistance, even with an antiauthoritarian flavour in line with Gülen’s criticisms against Erdogan during the uprising.

The political crisis of the Imam and the Sultan may well become the crisis of the state tomorrow considering that the two camps control different parts of the judiciary, the police, and other state organs which are pulled in different directions. Erdogans recent curbing of the judiciary and sackings of police chiefs are obviously actions carried out to gain total control over the respective bodies.

However, the movement seems to have the intelligence to refuse choosing sides in this crisis, something that was hinted on December 27 by the “Que Se Vayan Todos” banner featuring all the party leaders (except those of BDP/HDP) plus Fethullah Gülen. In this way, the movement is confronting the problematic of the mobilizing but fragile slogan demanding the resignation of the government. Anti-corruption protests were held also in Ankara, Adana, Mersin, Edirne, Izmir, Antakya, Çanakkale, Kocaeli and Hatay so things are on the move around the whole country.

The presence on the streets and squares is also a sign that the scandal isn’t for TV entertainment only and that there is a will to back the slogan of Gezi: “This is just the beginning.” December 27 was preceded by a manifestation in Kadiköy a week earlier organized by the public assemblies (the forum, some of them are still producing encounters and conflict), the groups against neoliberal urban transformation and the defense of the northern forests of Istanbul. Thousands gathered to reclaim Istanbul, its neighborhoods, open spaces, and forests under the rallying cries of solidarity, assembly, association against the limitless sale of common spaces to profit from redevelopment plans, and the commodification of everything.

Political parties and the old left showed up too for the call of the social movements. The red, green and yellow colours of the manifestation for the revolution in Rojava in Kadiköy on November 24 were also present on the square December 22 proving that the Kurdish movement is a lasting component of the movement. And yes, so are some less inspiring elements supporting the ancien régime though the agenda is fortunately not set by these red and white ulusalcı (Turkish ultra-nationalists). The surprising scenes of Gezi when we saw flags of Öcalan and Atatürk waving in the same crowd seem, in any case, here to stay. The Erdogan-Gülen split was commented upon in a Kurdish daily on December

28, two years on the day after the massacre: “We know both of you from Roboski” leaving little to say on the Kurd’s stance on the Sultan-Imam conflict.

The corruption scandal further fueled the permitted manifestation on December 22 which at the end didn’t permit the check-point set up by the police that one had to pass (after being searched) in order to arrive at the square in Kadiköy – it was torn down and police were eventually pushed away from the area after clashes (more clashes followed later the same evening). The roads and spaces around the designated area were thus liberated proving that the social movements aren’t just objects of police repression in a depressive post-Gezi era but also protagonists in the continuing practices of redefining the urban spaces.

Kadiköy has changed during the past years from being a student and family district to become the home of a considerable part of the cognitive proletariat of Gezi pushed out from the Taksim area by the politics of rent, speculation and gentrification. No wonder then, that Kadiköy has become the area of the first and only occupied social center in Turkey and a place of aggregation that inspires many. Perhaps can the territoriality of the Kadiköy experience inspire the movement that after Gezi has been looking for new weapons. Too often, it seems, the Turkish Left finds themselves trapped in ideological terrains with little or no focus on the territories and the resources. If the corruption scandal can be used as a moment of reclaiming spaces and income rather than calling (with a sometimes disturbing moralist tone) for juridical measures, perhaps it can open up for paths of recomposition. In any case, the answer to this crisis and the one yet to come is to be found in the streets.