If two policemen die

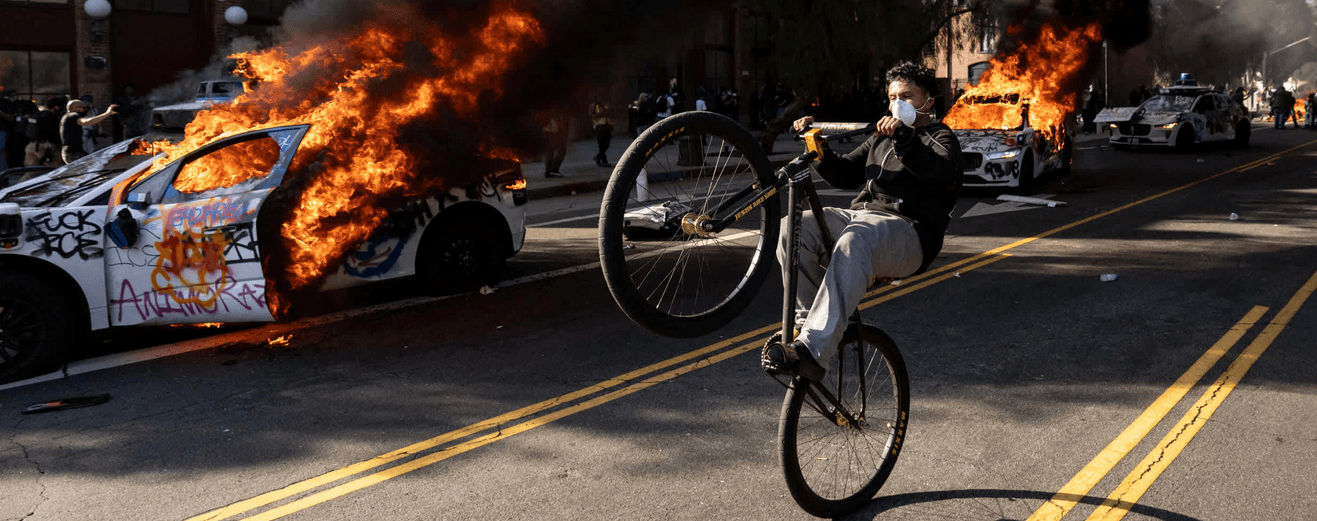

Certainly, the background is different. In the United States police murders of black people (and not only them) goes on undisturbed and, from this summer, a widespread and deep-rooted protest movement – that enjoys the sympathies of also many white people and surely of the Hispanic community – is raising. A mobilization that put in a corner the democratic representatives: Obama could not but admit that a common sense of injustice among many Americans in regard to the conduct of judges and police does exist. De Blasio had to address a most sensitive city as New York is, by going even beyond that: even by saying that the black boys, even if they behave “well”, have to look out for police when they come back home in the evening (here’s the reason of the criticism against him). A racial background that expresses an historical-symbolic legacy that does not exist in Italy (and, more generally, in Europe) or expresses itself in completely different forms. Yet, the factual analogy between forms or episodes of disconnection between police officers and institutional politics remains.

Let’s suggest an interpretation: police officers have been for years now increasingly affected by particularly aggressive beliefs. They deem themselves to be the sole bulwarks of the status quo and they realize that, without their violence, the institutional system would not be able to defend itself. These are no more times of relative social peace, these are neither the Nineties nor the bleak early 2000s anymore. The moral and political legitimateness of those in power is at its lowest ever, especially in the West. The agents engaging in public order feel it. Their first reaction is one of resentment against what they deem to be a disproportionate salary compensation and unacceptable working conditions – less in terms of workload and stress than of the political relevance of their roles in preserving public order. The consequent reaction is their unavailability to accept criticism, let alone when it comes from those politicians, whose defence constitutes the overall and (more depressing) meaning of their job.

All of this was born also out of the institutional forces’ (and their media supporters’) need to entrench public opinion not around a political project of power (those were the “ideologies”), but around negativeness and fear – all that was left to the capitalist forces after the victory of 1989. Fear of foreigners that blow themselves up or invade our territories in their millions, but also of the madmen, the fanatics and the desperates ready to slice our throats at any street corner. We know how this media and cultural hype made headways in the collective representations of the last fifteen years, until the justification of the despicable farce of the army in the streets in Italy, the disturbing militarization of police and public life in the United States, the literal invasion of the public places by the police and the army in France. He who became a soldier, but also he who joined the police in these years, believes to be the saviour of the people, because he reads everyday on the newspapers that so it is. The current generation of policemen is, in the West, a mixture of self-exaltation, fanaticism and nihilism, lack of ideals and rabid search for justifications.

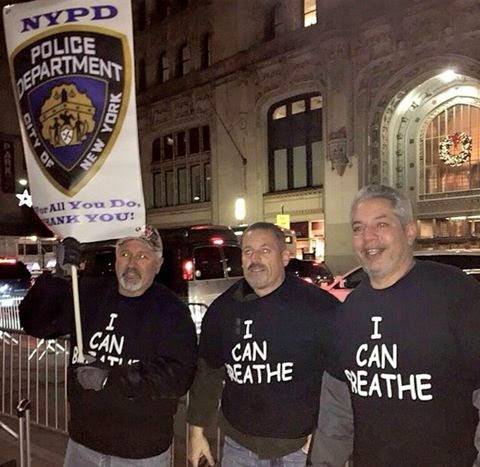

This mix generally explains the violence, but also the enthusiasm, with which these individuals assault us during demonstrations – which maybe are, it is worth bearing in mind, the only moments (partially also in the stadium) in which they are collectively addressed for what they really are. The problem with many of them, actually, is that they understand very well what we want to say when we address them as infamous; and this awareness of the ethical problem that increasingly makes its way among people about the real role of the police (let’s think about the dirty work of dislodgements and evictions) represents, in perspective, a problem for the institutions. That is also the reason why it is so important, today in New York, to set up this massive spectacularization on the funerals of the two slain agents. The institutions know how much widespread the perplexity, if not the open hostility, towards the social role of police is – in different global regions and contexts. Many are led to ponder about it, in New York or elsewhere; and even more serious contrasts can arise within the societies.

It is possible that, in the coming years, the importance of police forces will become so great for the institutions – as the only physical wall to stand against their potential destruction – that they will become partially independent powers of their own, as already, traditionally, the army is. Hyperliberalism destroys any social mediation, except for the threat of violence. Processes of partial privatization of the repressive duty are already underway, by contracting to private companies increasingly important slices of urban control. In the Arab, Turkish and Greek revolts the police forces showed to be willing or capable to use, in various ways and different directions, their political weight. The distance that separates military power and police power will be inclined to inevitably shrink: police duties have increasingly been, for years now, duties of latent civil war; those of the armies are increasingly roles of international police. It is not important the immediate extent of the amount of violence that is released on the people: the modern institutions are pre-emptive institutions. Their duty is to prevent that something kicks off. The police violence works today especially as a threat in response to another threat. We are living in an age of latencies.

These threats that face each other are political facts. The police threat is a constant one: it does not particularly nest itself in this or that patrol car, in this or that squad, in this or that officer or agent. The attitude that we have to show towards the institution as well as towards the single policeman is always a political one. Even when a police car stands still between two avenues in Brooklyn, in the ghetto neighbourhood that peculiarly borders the one of the nightlife, the policeman reminds the population the limits of their possibilities. The policeman chose its side, and knows that sometimes the possibilities exceed their limits. The policeman, in Europe or America, be it good or bad, white, black or blue-spotted, hopes the real to match the possible for today as well, in order to win his bread. The policeman, in Rome as in Paris, in Istanbul as in New York, is a man that had reneged his independence in exchange for two cents, that sold his arms and eyes to the power to avoid the common fate of social precarity and possible freedom of the people around him. We do not stop to look at this individual in a political way. Every policeman is an enemy of ours.

InfoAut

Ti è piaciuto questo articolo? Infoaut è un network indipendente che si basa sul lavoro volontario e militante di molte persone. Puoi darci una mano diffondendo i nostri articoli, approfondimenti e reportage ad un pubblico il più vasto possibile e supportarci iscrivendoti al nostro canale telegram, o seguendo le nostre pagine social di facebook, instagram e youtube.