Local elections in Italy: a setback for the PD party-system

After a most socially cold autumn and winter, with no big strike called by mainstream unions and few occasions for autonomous movements to challenge the Renzi government spell on the country, some early cracks started to show up in the Democratic Party (PD) narrative and bloc.

The social onslaught against squatters (Piano Casa, canceling rights and services for people living in occupied buildings), students (Buona Scuola, re-introducing class-driven meritocracy and underage labour), workers (Jobs Act, lowering safeguards and easing layoffs) and territories (Sblocca Italia, hitting frameworks for legal opposition to works and infrastructure projects threatening environment) in the first two years of Renzi government was followed by pro-bank legislation and dismantling of residual welfare state framework, also in the effort of reshaping the PD as a natural government party drawing votes from the whole “moderate” political spectrum. Renzi’s hubris against an extremely watered-down referendum about offshore drillings also alienated an additional share of the traditional leftist electorate.

Then local elections last weekend came; the event, affecting 5 cities among Italy’s biggest, was marked by growing abstention rate (now at an average 60%, down from 75% and even 80% just ten years ago) and unability to achieve outright victories for all the candidates: these two facts forebode weak and poorly legitimated administrations, and thus potential for autonomous antagonist movements to make a breakthrough.

In Bologna, a PD stronghold, there were setbacks for all the institutional parties: the incumbent mayor was not re-elected at the first round, the catch-all Five Star Movement (M5S) did not make it to the second and the radical left lost votes in comparison to 2011. But, most importantly, the right-wing parties were met through the year with steady social opposition by the city; and, in the very last days of the electoral campaign, their national leader Salvini was prevented by a grassroots mobilization organized by autonomous collectives and associations from giving a speech in the university area he boasted to visit.

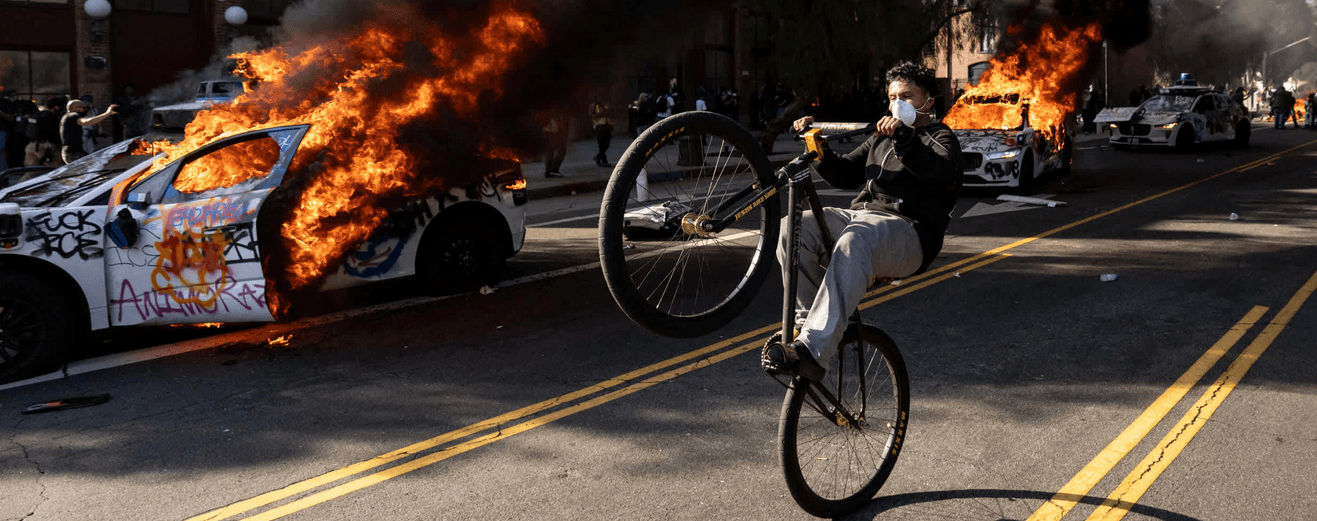

Also in Turin the dominant PD system (backed by the big Intesa San Paolo bank, the residual FCA automotive management, la Stampa daily and other powers that be) was shaken and forced to contend the run-off to a local M5S candidate capitalizing on popular opposition to great works such as the TAV in the Val Susa metropolitan area and discontent with the city’s huge debt burden and administration, which exploded in the riots of December 9, 2013.

In Rome the M5S prevailed, boosted by popular exasperation against the traditional parties (with most prominent cadres of the latter being involved in the Mafia Capitale network/affaire); the fascist right was crushed (Casa Pound, Forza Nuova, the anti-abortion Il Popolo della Famiglia list) and the division in the mainstream right-wing parties enabled a low-profile PD candidate to run in the second round.

In Naples the incumbent administration headed by Luigi De Magistris – a former public prosecutor turned politician – played the card of “antagonism” against national government interests, garnering across-the-board consensus (yet a reduced one in comparison to 2011) and achieving a first easy victory against traditional parties contenders, whose electoral campaign was riddled with irregularities, bribery and proximity with organized crime interests.

Milan was the most unfavourable theatre for social movements, being still fresh the chauvinistic rallying mood of the city middle class around the EXPO global event: its former top manager – Giuseppe Sala, the PD candidate – votes matched those of his rival, a bureaucratic technocrat in former centre-right administrations, distancing all the other options.

Now the Constitutional Reform referendum in October looms on the horizon – by promising a showdown between the government bill, bent on

making structural the outright neoliberal development of the last five years (a tantamount to what happened in other European Mediterranean

countries), and its many opponents. An event that, in order to produce the grassroots disruption Italy badly needs, has to feature also a strong movement against austerity, war and a conveniently permanent crisis.

Ti è piaciuto questo articolo? Infoaut è un network indipendente che si basa sul lavoro volontario e militante di molte persone. Puoi darci una mano diffondendo i nostri articoli, approfondimenti e reportage ad un pubblico il più vasto possibile e supportarci iscrivendoti al nostro canale telegram, o seguendo le nostre pagine social di facebook, instagram e youtube.