Politicity of the Riot

Transformations of the social reality depend on a mix of factors which render partial any unequivocal determination. To come to terms with the unshakeable uneasiness of the human world, in the contemporary critical geography, one often refers to a phenomenon of “turbulence”. Such terminology, which in the scientific lexicon indicates the wild and whirling flows produced as a result of the meeting of great currents of air, pointedly, is mobilised to depict, in a metaphorical sense, a sense of agitation and restlessness. To coin this metaphorical usage of the term was none other than Marx, who, in a speech given in London in 1856, described Europe, freshly struck by the revolutions of 1848, as a crucible in which the apparent solidity of the surface – the “dry crust of European society” – was broken, allowing an ocean of liquid material to emerge that was ready to circulate throughout the continent, and to break it up into many small fragments.

Phenomena like turbulence, therefore, describe a hybrid state of agitation, which eludes the binary logic of order/disorder and that perennially characterises social and political life. A riot is an exemplary example: often removed and foreclosed* from the political genealogies of the present, a riot is the mark of the existence and action of a subjectivity that was never reintegrated into the figure of the citizen. As the historian Jean Nicolas points out in a monumental work classifying popular and urban rebellions in the Ancien Régime age in France, in fact, “the archetype of urbane confrontation” is an amalgam of bodies, cries and violent acts that the political syntax of modernity is unable to decipher. A convulsive, amorphous and powerful aggregate: a mirror-like figure with respect to the individual citizen.1 Intuition that becomes fundamental in the light of the conflicting players, often strongly racialised, who accompany the formation of the grand contemporary metropolises.

To this end, by recognizing in the riot a systemic phenomenon of the contemporary age, the antropologist Alain Bertho provides a detailed chronology of the urban revolts that affected Europe and the United States in the period ranging from 1968 to 2009 and, at the same time, he develops a hyphothesis of political periodization starting from the analysis of the main motivations that, on a case-by-case basis, stand at the core of insurrectional explosion.2 Between the seventies and the eighties the riot retained an explicitly political character, and in the nineties it becomes a form of spontaneous and mass reaction to the surge of police violence in the working class neighbourhoods of the grand metropolises, at the turn of the millennium it becomes impossible to identify its main characteristics: several real territorial dynamics that materialise increasingly explosive social contradictions are joined by openly political motivations – as in the case of the anti-globalization movements of Seattle and Genoa. The riot becomes constituently heterogeneous as it expresses in itself a “subjective philosophy of rage”.

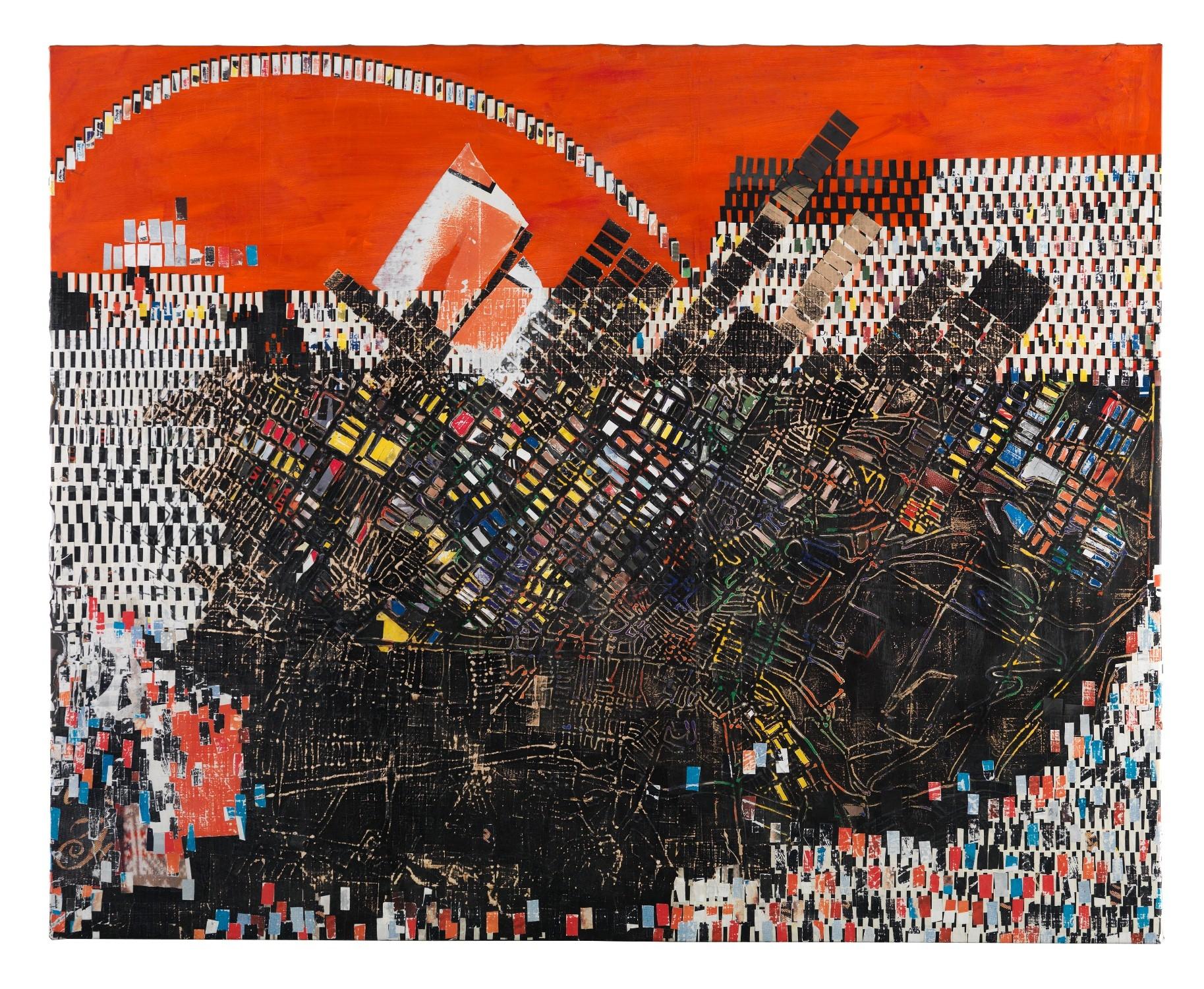

The more or less intense eruptions of rage, more or less medialized, that on a regular basis inflame the poor neighbourhoods of the modern metropolises at different latitudes and longitudes – the previously mentioned Bertho, since 2009, provides an accurate account on a trans-national scale, even if not a properly global one3 – possess, notwithstanding the uniqueness of the cases, a kind of “synchronicity of the imagery”, internal cross-references, correlations and resemblances that allow a unitary political consideration over the whole. Currently, within the contemporary metropolis, a battleground avoiding the most consolidated political categories opens up: a new urban proletariat, fragmented in itself, strongly racialised and drastically pauperized, opens a gash on an “illegal subjective landscape”.

From this point of view, the riot is always a political act. Its translation, in terms of “urban violence”(a category that decrees the depoliticisation of the principle as well as its preventive criminalisation) answers a strategy of contrast articulated and driven by a mixed aggregate of military and police (in the same instance pertaining to the state and above it, to the public and the private) and whose necessary corollary is the integration of a wide and pervasive informative apparatus. If, already in Foucault, in his studies regarding the transformation of the techniques of government in the course of modernity, there is stated, with clarity, the necessity of interrogating the relationship between production and the government of territories, control of social reproduction and evolution of the police, here one faces, however, the recasting of the question in the light of a comprehensive economic and political reorganisation punctuated by the two phases, ‘rock back‘, and ‘roll out’ of neoliberalism.

In this regard there rests particular importance in tracing the nexus that subsists amidst the formation of an urban business politics as the fundamental component of a capitalist restructuring that took place between the eighties and the nineties, somewhat precisely at the hinge point between the destruens and costruens phases of the “new global logic”, and the intensity of the insurrectional shocks that strike, albeit with some significant local specificities, the space of north Atlantic capitalism of the same period. As Loïc Wacquant observes based on the comparative examination of three paradigmatic cases – the émeutes of Vaulx-en-Velin in 1990 and the riots of Bristol and Los Angeles in 1992 – the urban uprisings mix two logics that are connected between themselves: ‘a logic of a protest against ethnic injustice’, and a ‘logic of class’, and write themselves on the inside of a process of overall redefinition of metropolitan geographies.

Far from represent a pre-modern legacy (an unhistorical leftover of untameable passions like a toxic narration, all too obviously corrupted by its own incurable racism would imply relegating the riot to a sphere of irrationality and barbarism representing an almost obsessive orderliness – as always obsessive are the aftermaths of the past that have been poorly re-elaborated), on the contrary, the seismic shocks produced by urban mobilisations are an integral part of a process of dissolution of the double bond between capitalism, citizenship and metropolitan development; a double bond that has characterised a long phase of expansion of the city, in other words the nexus that connects citizenship to salary and that, which is in turn intertwined to the first, that articulation of citizenship and consumption.

Just as Wacquant suggests, in fact, the “infrapolitical protest” that expresses itself in urban revolt should be conceived in the context of a process of “desocialisation of waged work” (that is the exhausting of a dispositif affecting uniting political integration founded on, in the last analysis, waged work) and interpreted in the context of overall social transformations. It is a matter of intersecting different perspectives of analysis and, above all, avoiding a kind of hermeneutic shortcut that appeals to the rhetoric of the ‘shock‘ and of the event. The episodes of urban insurrection, in fact, don’t constitute isolated episodes, disconnected by the time and space of the every-day, as much as, rather, a form of intensified and depersonalised expression of the tensions that traverse the body of the metropolis. In other words, the violence released by the riot has a systemic nature. The most interesting aspect, from this point of view, regards the subjectivity which expresses itself within it: actually, as has been stated, if every act of insurrection displays a “(socio)logical reaction against a structural violence”, its political meaning remains an open issue.

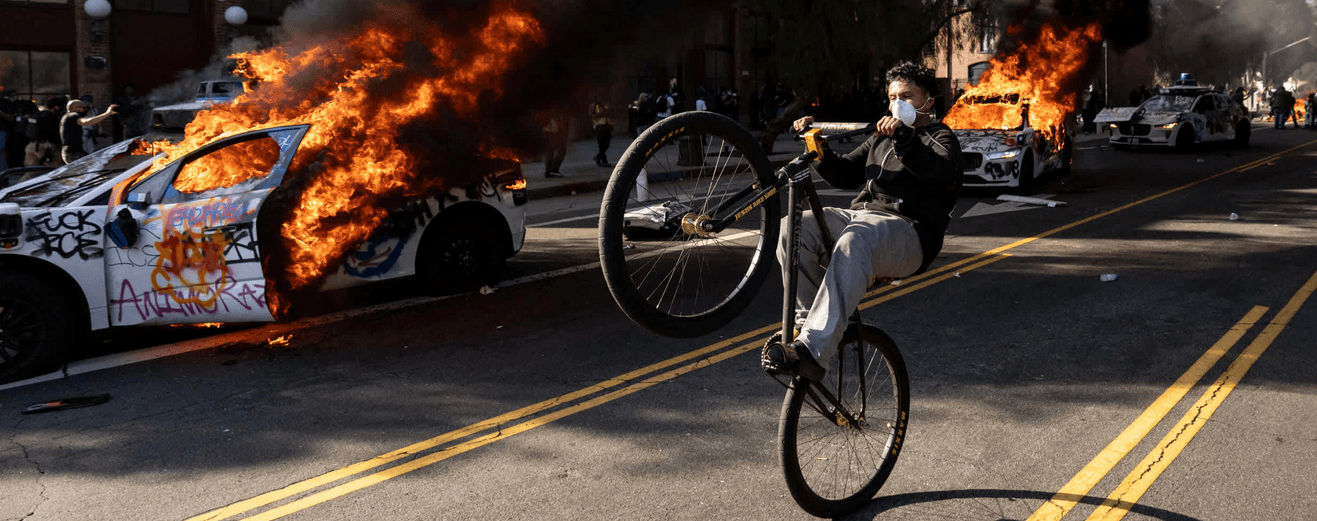

The political history of the riot, indeed, seems to gain the utmost interest not only because of the fact that, at least starting from the Nineties, the urban insurrection became a recursive event, and a widely spectacularized one on a global level, with all its phenomenological paraphernalia – burning cars, vandalized buildings, hooded faces, melting bodies that pour from the urban framework, broken glasses, alarms and tear gas, looting, transfiguration of urban street furniture in to makeshift barricades, excerpts of barely articulated discourse sprayed on the city walls – but, especially, as a repository of material born out of a description of the complexity of the present moment. Maybe one can hazard a guess, according to which the insurrection of the metropolis, in its absolutely heterogeneous form, illuminates a great deal of something unconceived – unresolved and foreclosed – in the political perspectives, and makes it stand out both in terms of limits (in this case as a kind of negative criticism) and in terms of possibility (and therefore as a positive criticism). Imagery and imagination at the service of that “minor line” of political thought that makes conflict, instead of contract, the generative source of the social relations and the frameworks of power.

Notes

1 J. Nicolas, La rébellion française. Mouvements populaires et conscience sociale 1661-1789, Gallimard, Paris 2008 (Prima ed. 2002).

2 A. Bertho, Le temps des émeutes, Bayard, Paris 2009.

3 Check: http://berthoalain.com

Ti è piaciuto questo articolo? Infoaut è un network indipendente che si basa sul lavoro volontario e militante di molte persone. Puoi darci una mano diffondendo i nostri articoli, approfondimenti e reportage ad un pubblico il più vasto possibile e supportarci iscrivendoti al nostro canale telegram, o seguendo le nostre pagine social di facebook, instagram e youtube.