Banlieue, Insurrection, Call of ISIS

An help to answer our questions, if we are able to see to its striking moment in a longer story, could be found in a recent great event that only few have the courage to confront: the 2005 banlieue insurrection when the suburbs, often also the city centers, were turned up-side down. We are dealing with a great charge into the present that also questions us -especially us, it should be said. We, the participators in the collective project of a radical transformation of the existing conditions.

According to the surveys made visible by the press, most of the French citizens that recently have left for the theatres of civil wars are residents in the suburbs -the so-called Sensitive Urban Zones (ZUS). They are between 20 and 40 years old and have almost in every case previously been judged and sentenced for “infractions towards people entrusted with public authority” (IPDAP). The authors of the Charlie massacre neatly match the figure that official statistics and information describe as the banlieusard. It looks as if more than just a few young Parisians and residents of the French banlieues have turned their faces to the flag of ISIS or, in the most ambivalent and contradictory ways, have become sympathizers of it after having participated in the insurrection.

After all, the identity of the banlieuesard of 2000 has been built in the comparison/clash with the Military, the Police, and the Judiciary, as well as in the reaction against the destructive nihilism of consumption and the desertification of the suburbs of neoliberal France. This is the interpretation we are proposing. But how? On closer inspection, we are dealing with a proletarian identity that, when taking shape, was and still is in search for a general orientation in terms of a political project, ethical values and a long-term perspective. Lacking a better alternative, some turned towards the Islamic State or, in general, towards the proposal of radical Islamism (mainly the present factions that proved victorious after the defeat of the Demo-Islamism of the brotherhood).

The religious element was almost completely absent during the 2005 insurrection. The efforts of the Government and certain parts of the press failed miserably to impose the paradigm of the clash of civilizations -dozens of tear gas canisters that were launched into the suburbian mosques by riot police didn’t have the desired effect. Therefore, the vocabulary put to use in the metropolitan battle consisted of labels such as bandits, barbarians, foreigners, and scum. “La racaille” was the word Sarkozy used, at that time Minister of Internal Affairs, right before the National State of Emergency was declared. Actually, it was about young French citizens, children of the first, second, third generation migrants living in the banlieue that night after night of clashes smashed the French republican ideology into pieces. An ideology which, by means of the jus soli applied in France since 1851 , formally held on to a assimilationist policy that declared itself ready to grant full citizenship and the enjoyment of certain material conditions in exchange for the neutralization of the ethno-cultural identity of origins.

This policy was never active without flaming conflicts and political and trade-unionist clashes during the first industrialization of the country when its object consisted of a migrant workforce to a greater extent coming from other European countries such as Italy, Spain, Portugal, and Belgium. When the time came for the first political organizations of post-colonial immigration, such as the Movement of Arab Workers (MTA) in the 1970’s, the policy had a poor look in the eyes of its large class segment. In 2005, the policy was definitely a dead dog wearily dragged into the talk shows or the columns of a few newspapers by the elite.

Already during the socialist government of Rochard (1985-1989), public resources destined for welfare in the banlieues began to diminuish, and the March for Equality and Against Racism that began in 1983 was completely disactivated during this period. Reaching all the major cities of l’Hexagone, the march posed the political problem of life conditions in the suburbs, scarcity of welfare, and the relative increase of racism pouring out on the residents of the banlieues from the institutions. Despite the Left’s proclaims and solicitudes, this situation continued to accelerate until the 90’s. It was during this decade that we, for the last time, could see an organized form of social conflict and clash. The Immigration and Banlieue Movement (MIB) were very active in the struggles over the right to housing, access to welfare, self-defense against racist police violence of above all the Anti-Crime Brigades (BAC) -special forces responsible of violence, brutality and racist murders in the French suburbs.

At the dawn of the last century, MIB was destroyed with repression and, in some rare cases, institutional co-optation. This left the banlieue without any explicit political instruments (rap being an exception) as it was subjected to neoliberal desertification.

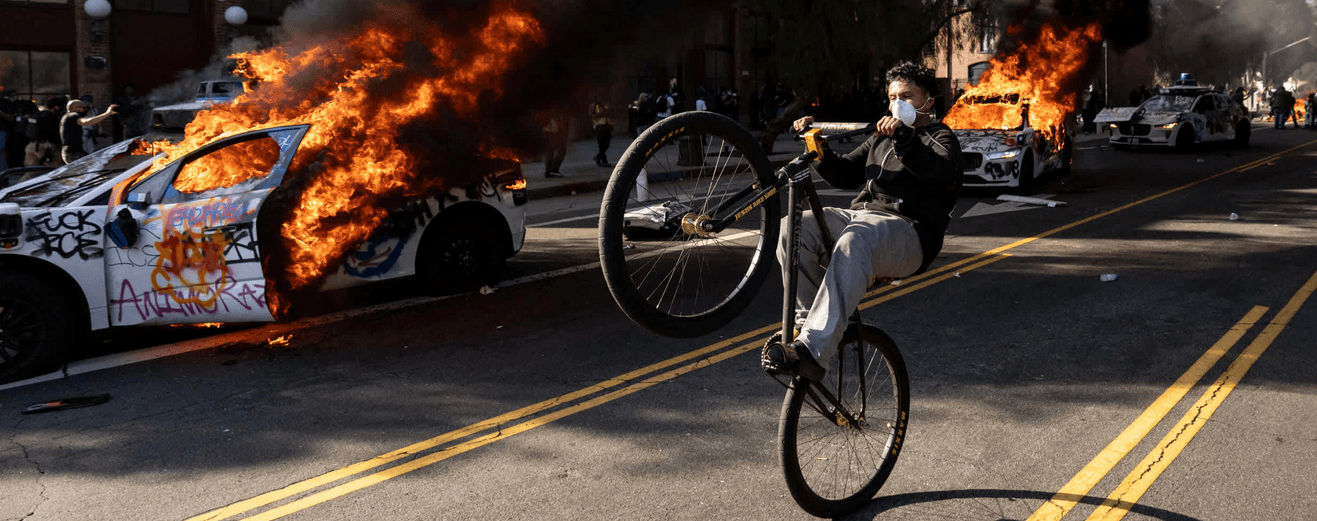

The definite end of social mobility, the absence of services, lack of access to healthcare and to a desired educational system, exclusion from urban mobility, rise of unemployment and precarity augmented social conflict. The banlieusards found themselves through latent antagonist forms of organisation in a dialectic with the police and the legal system. The original and ambivalent figure of the “partisan” of the suburbs, as the victim of abuses or in the leading role for revenge, takes shape in the juridico-police sphere. This figure uses web platforms for the first hip hop blogs and sms in order to organize the clash, snorts speed on the barricades, shouts at neoliberalism by using rap and graffiti, destroys cars and public transport, sets schools and offices for municipal service on fire. By building barricade after barricade, s/he tries to reach the center of the city, to the triumph over promised consumption guarded by the blows and kicks of the BAC and the prison of the French court houses.

This is the “tragic partisan torn apart by political solitude” from the banlieue of 2005. It’s rough composition was pregnant with ambivalences already back then and exposed to unexpected polarizations. Left without a Pugachev or platforms of claims, the banlieusard set vehicles to fire, smashed public and private buildings, and attacked the police. S/he moved within the dialectic that produced and reproduced the own identity in relation to the military, the police and the judiciary. In the midst of the desertification of the neoliberal metropolitan banlieue, s/he made way through identitarian methods of counterposition against the only forms in which the State ever presented itself in the banlieues: armed urban frontiers, repression and legal processes.

The 2005 autumn of clashes – sparked by the murder of two teenagers during a police hunt in Saint Denis (a Parisian neighbourhood, home to the two main perpetrators of the Charlie massacre)- closed down, from a subjective point of view, a cycle of almost fourty years of struggle in the banlieue. Extraordinary spaces of possibility for new forms of organization of conflict and experimentation of collective projects could have been opened up. But the movement against the war in Iraq (an outcome of the counter summit alterglobalization movement and the Left) or the movement of precarious workers and students never sat their foot in the banlieues. The already then visible divergence between Left, Ultra-Left, and Banlieue has widened with time. In February 2006, the high school and university students mobilize against the First Employment Contract (CPE), which would have introduced lay-offs without any justification of young workers between 18 and 25 years of age. “The banlieue question” was not politically considered by the composition of the movement against precarity which, when the battle was eventually won, flowed back into the classrooms and faculties.

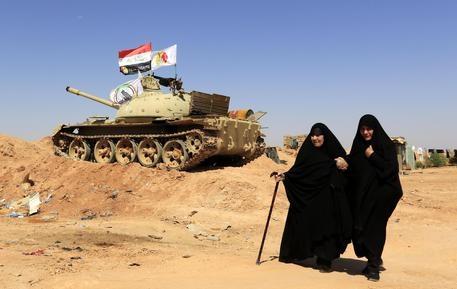

The 2005 insurrection rendered its implicit demands visible and was explicitly characterized by a belligerent dialectic of banlieusards-police, or banlieuesards-repression. This consolidated an identity that put its bets on a military level. We are departing from this analysis when considering the orientation of a part of this composition towards the CALL OF DUTY of ISIS -where the jihadist aesthetic in a twisted way satisfies the ambivalent desire of access to consumption and the affirmation of social justice is codified by the general promise of the divine law to be realized on Earth. We invite our Italian readers to closely consider the in-dept analysis CROCEFISSIONI RIPRESA DALLO SMARTPHONE. ANTROPOLOGIA POLITICA DELL’ISIS by Nique la Police for Senza Soste which construes the political and antropological aesthetics of radical Islamism as promoted by ISIS. The text explains -among other things- how the images of postcards from the Caliphate portray a calm sweet life in the land of Cockaigne that blends with the Flames of War of crucifixions, slave markets and beheadings. Images that offer a (perverse) satisfaction of income and justice that never was to be found in the banlieues but now await in the new promised land. It is clear, also from this point of view, how the paradigm of the”clash of civilizations” works as a kind of activator in the clash within civilization by expunging parameters of class and the possibility for liberation and proletarian self-determination. Essentially, the paradigm of the “clash of civilizations” violently turns class conflict into an intra-capitalist conflict that confessionalizes and ethnicizes the clash. This paradigm is also immediately inherent in the geopolitical game of interests of various imperialisms.

The French banlieue has never faced a political process of Islamization up until today and the composition of the young suburbian proletariat has often detached itself from the traditional forms of Islam as practiced by their families. The magnetic call of ISIS works above all on the desertification of the territory and the absence of a radical and revolutionary project in line with the needs, problems and expectations of the suburbian population. The paradox we are facing lies in the fact that with the revolutionary processes of 2011, also in the current outcome, large parts of the young proletariat and middle classes of North Africa and the Near East have abandoned, refused or entered into open conflict with the Demo-Islamist hypothesis. Looking at the actual numbers on the field, at least in the South and East Mediterrean, the call of ISIS has not moved much apart from the hard core pre-existing already before the advance of the Caliphate inbetween Syria and Iraq. Therefore, the Parisian banlieue and the tragic phenomenon that has surfaced in recent days are questioning us who, in line with the experience of Rojava, experiment with autonomy and antagonism. In order to avoid turning into witnesses to tragedies at home and supporters of triumphs abroad, our call is the attempt to answer by beginning with our own territories, according to our limits but also from the spaces of possibilities that -if not seized- could well become the territories of an enemy yet to come.

Ti è piaciuto questo articolo? Infoaut è un network indipendente che si basa sul lavoro volontario e militante di molte persone. Puoi darci una mano diffondendo i nostri articoli, approfondimenti e reportage ad un pubblico il più vasto possibile e supportarci iscrivendoti al nostro canale telegram, o seguendo le nostre pagine social di facebook, instagram e youtube.