Matteo Salvini’s new Northern League: enter the next right-wing, lepenist Italian project

Was it an unavoidable rise? No, it was not. A mix of internal organization and failure of other institutional opposition parties’ paved the way to the League comeback.

Between 2011 and 2012 the party was rocked by the demise of the Berlusconi government and by a string of scandals revolving around graft, embezzlement and nepotism by founder Umberto Bossi’s inner circle. The subsequent loss of political credibility and the simultaneous rise of the populist, catch-all Five Star Movement of maverick comedian Beppe Grillo marked significant setbacks for the party in several general and local elections – among which, the loss of the Piedmont region. The former minister of the Interior Roberto Maroni, which managed to get elected governor of Lombardia, then marginalized Bossi and successfully endorsed Matteo Salvini as the League’s next general secretary.

After a landslide victory in general elections, the Five Star Movement spectacularly withdrew from an all-out showdown with the institutions in 2013 – when, after the controversial re-election of former President of Republic Giorgio Napolitano, the corrupt Italian political system’s lord protector, scores of demonstrators from the movement’s base were ready to march on the Parliament. Then the Movement was plagued by internal purges, defections, and inability to affect the Letta and Renzi governments’ “reforms” blueprint, and was ultimately rebuffed in the 2014 European elections. Berlusconi’s party, which antagonized the Monti and Letta technocrats’ governments (going as far as endorsing a strong euro-skeptical platform against them) made a u-turn with the Renzi government – as the latter was less hostile to the media tycoon’s personal interests, and more attentive to establish a common institutional framework with him in order to secure a long-term, post-Berlusconist, hegemony.

Until then, Salvini was mostly notorious for his slanderous howls against Neapolitan citizens (the Northern League started out as a secessionist, anti-centralist party – before turning anti-migrants, and then anti-Europe) during a party convention. But he quickly set aside the residual goals for independence of Northern Italy regions, in order to occupy the traditionalist rights’ political space – championing a nationalist project alike to French Marine Le Pen’s. He subsequently became a great friend and ally of the Front National at an European level, promoting its same agenda.

Differently from the Five Star Movement (whose base swinged and swings between radical anti-corruption institutional stance and anti-system sentiment) Salvini was not antagonized by mainstream Italian media. At first he got some benign coverage from them and then, roughly after his big “Stop Invasion” demonstration in Milan against migrants last October (which rallied about 40.000 sympathizers) became their darling – embodying the perfect antagonist for Renzi. He also made a clever use of social media (not without outright buying followers and endorsements there) by engaging conservative and lumpen electorate through small-talk, stereotypical racist and law-and-order remarks. Still, he paid attention to traditional media too, appearing on all kind of broadcasts and even posing for a women’s magazine.

Meanhile, as the neoliberal character of the Democratic Party deepened, so did do the traditionalist, corporatist character of the Salvini (and in turn Northern League) discourse. Championing the interests of small farmers and entrepreneurs, whose exports to Russia were damaged by European sanctions following the war in Ukraine, he embraced a pro-Russian stance, longing to meet with Putin himself. He did also show authoritarian tendencies, praising the North Korean regime during an official visit to that country. As party frameworks, discipline and organization became much less coherent and monolithic (in the past year of Renzi government the Democratic Party lost thousands of its own members, still retaining the relative majority of the shrinking electorate) and much more volatile and centered around leaders (and their personalities and relations), Salvini made also some moves aimed at promoting his message beyond his immediately close support base. He tried to appropriate the Italian left iconic song ‘Bella Ciao’, turning its refrain against unruly migrant “invasors”; he welcomed the anti-austerity Tsipras government in Greece; and held his hand out to some fordist and corporatist sectors of the trade unions, hit hard by outsourcings, negative aftermath of the Fornero pension reform and hostility by the pro-business Renzi government. An apparently uncontested progression that secured Salvini around 14% of a potential general election vote (though in the last years both abstention and hostility towards institutional politics in Italy surged).

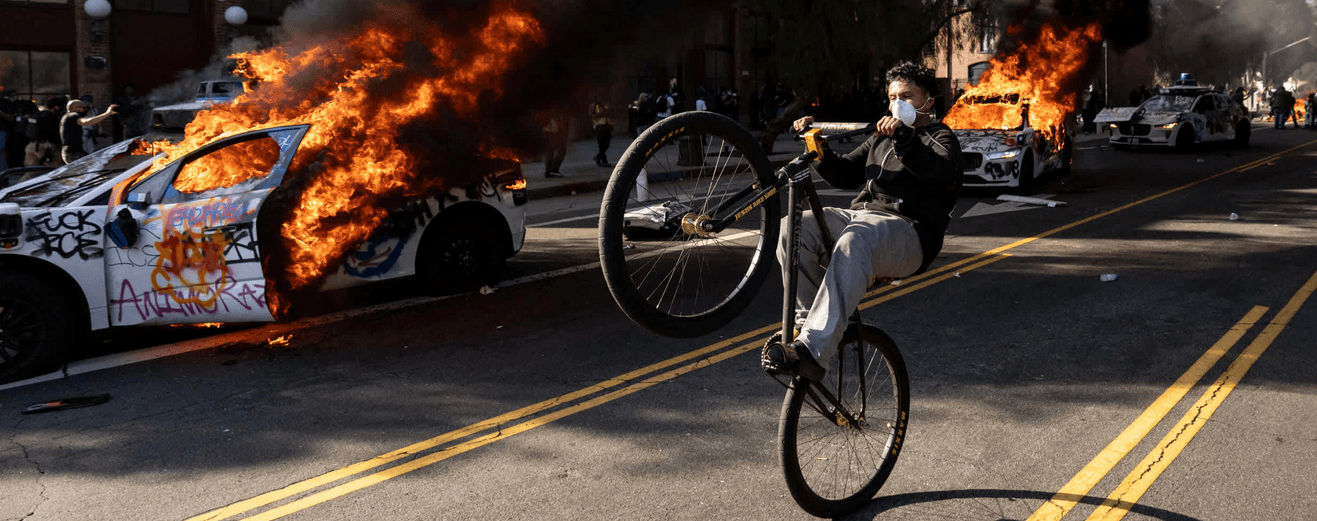

Then, what bulwark can stand against the Northern League secretary, in case of a breakdown of the Democratic Party rule? Burgeoning mestizo housing rights’ and logistics workers’ movements displayed a deep hostility against Salvini’s project, at times confronting Northern League militants – when the latter sided with capitalist bosses in Emilia Romagna against warehouses’ migrant employees. In spite of Salvini’s attempts to organize lists and cartels of politicians sympathetic to him in Southern Italy, popular sentiment against him there stays strong, also fueled by an ongoing militant debate on Southern identity and historical role in the framework of the Italian state development. Massive antifascist response to the almost lethal ambush against a militant of the Dordoni autonomous social centre in Cremona by the Salvini neofascist sidekicks of Casa Pound showed that, even on military terms, the League will be met by a relentless opposition. The battle against the newest far-right, racist vessel in Italy has just begun.

Ti è piaciuto questo articolo? Infoaut è un network indipendente che si basa sul lavoro volontario e militante di molte persone. Puoi darci una mano diffondendo i nostri articoli, approfondimenti e reportage ad un pubblico il più vasto possibile e supportarci iscrivendoti al nostro canale telegram, o seguendo le nostre pagine social di facebook, instagram e youtube.