Future prospects, inside and against Euro-austerity

The European elections and then the Italian 6-months’ Presidency term. The agenda of the counterpart set the “European Union” topic even in the Italian public debate. It looks like that the movements that have been opposing its initiative for decades have clearer ideas than the power or powerless political elites – that rediscover the Euro when the Capitalist calls to attention.

Without going back too far, we learnt to know the European Union of the balanced-budget constitutional provisions, of the grants to the banks and of the other criteria of “stability” and “governability” of its constitutionally ordo-liberal system. An institution that increasingly estranged any “democratic decision-making” forms (even the cronyist and bogus ones of representative politics) and of collective control on wealth redistribution embracing an alleged, ideological rationality of the markets. Markets in which the value of the quotations is notoriously influenced (if not preconceived) by clear players and decision-making elites and think-tanks – often intertwined with political power in an unshakeable self-referential duo.

Still, a non-monolithical European Union by now – at least as regards the sub-community and state-level profile of its political system -in terms of key interests, governance capabilities and positioning to capitalize on the cherished economic recovery. The UK increasingly calls it quits from any integration processes which do not legitimize the most liberalised and wanton financial economy (a sector in which it enjoys an advantageous position). France ventures itself into an hyper-active foreign policy, in order to stop up the serious internal legitimacy crisis and the onslaught of hedge funds, that slowly tarnish the basis of its welfare state and of its standing among the “core” European countries. Germany holds up thanks to its internal demand and the back-in-power SPD, having forgotten its serious responsibilities in the Hartz reform – in cutting down unemployment subsidies by introducing new forms of precarious work, with a social impact comparable to the Italian Biagi Law [1] – could now claim some poisonous social-democratic crumb. East European countries are worn down by corruption and southern ones retain compulsory constraints in their public spending choices. The whole EU project suffers the weight of the swords of Damocles of the Scottish and Catalan referenda in September and October. Meanwhile, the Banking Union agreement of last December is a true masterpiece of opportunism and cynicism: a time range between 2016 and 2025 has been set for its enforcement – after which the banks will be subject to fixed amounts of capital requirements to avoid default, then being less inclined towards granting loans.

Meanwhile the states will still be the ones to pay for potential bank defaults – a not so unlikely chance, given the political and economic global tensions and the many sleeping financial bubbles in emerging markets. It would be the end of the line for Italy in particular, a country already oppressed by the yearly 50 billions € to be paid off for ten years in order to bring public debt under control – according to the now constitutionally enshrined Fiscal Compact agreement (to make a comparison, the infamous Monti government “SalvaItalia” budget law amounted to a mere 20 billions euros – of overall public spending, not plain debt repayment!). Moreover, considering obligations to pursue a balanced budget and reduce deficit (with an over-ten years long feeble growth) and lacking either political will or future occasions to renegotiate treaties, it is difficult to imagine to not getting over this situation without new burdens to be inflicted upon taxpayers.

In front of this harsh reality, which exit strategies were devised? The poor Tsipras (targeted by recent ill-fated Italian-style endorsements) that, with his Syriza, would represent the European vanguard of re-negotiation has nothing but a tiny share of public opinion (lumped by the so-called alternative left) on his side. A perennially defeated left now reduced to a ceremonial role and used, depending on the cases, by the benevolent hands of the socialist European parties.[2] In Italy the tragi-comic outcome of the “orange mayors” and of the Bersani-Vendola duo have to be taken into account.[3] But also, last but not least, the green light of the La Repubblica party to the European Syriza, thanks to Barbara Spinelli – the heretical goddaughter of De Benedetti, whose chatter guarantee the pluralist image of the rag’s central committee.[4]

From where the Euro-Syriza could draw social and political strenght and not public opinion strenght (and, furthermore, a narrow one) to re-negotiate the treaties that define the EU, it remains a mystery, or better a farce that the movements’ collective intelligence promptly realized. Not by any chance, as many correctly noted, the issue is object of a great and blatant indifference, and only arouses political elites. Starting from the analysis of behaviours of refusal and hostility to the capitalist crisis, the EU is (fittingly!) perceived as an enemy, and it is on this relation of enmity that the future prospects of a new and adequate borderless solidarity have to be methodically and patiently built. As of today, Euro-struggles do not exist! Short of mistaking for “struggles” some hyphotheses of political initiative, aimed to the upcoming European elections.

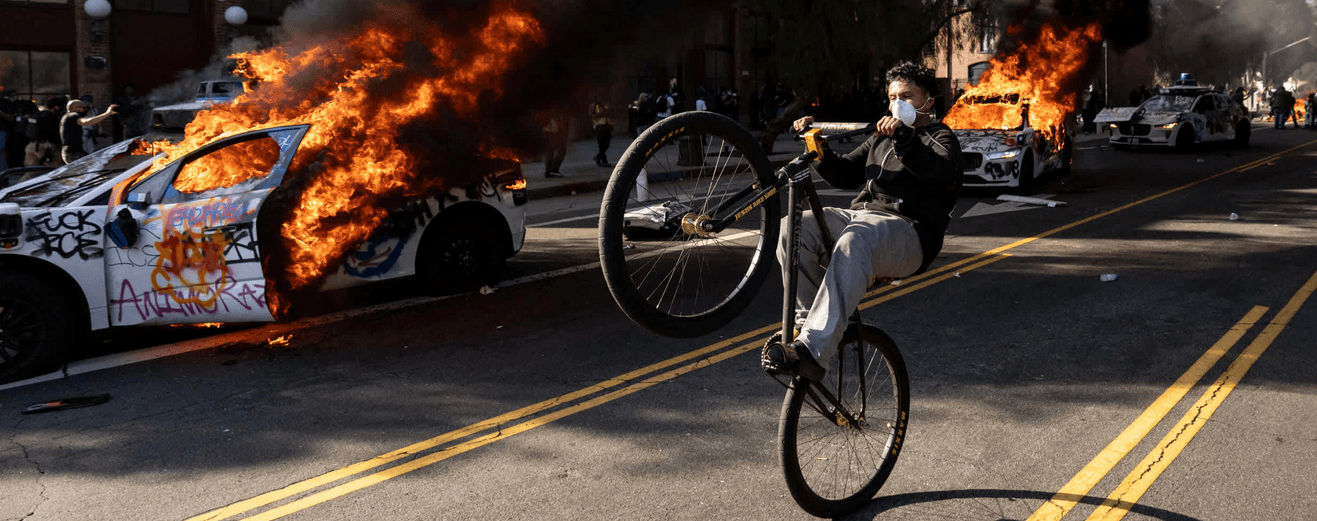

If, to this day, among fiscal compact agreements, high geopolitical tensions and financial bubbles the EU and global order (conceived as allocation of rents and profits) looks quite far from stability (a given only opposed by a mostly cross-class as opportunist “liberal” optimism) an antagonist point of view has to seize, as a strategical initiative space, the one scarred by the conflicts produced by the middle class erosion (to be intended as a political tool of capitalist social cohesiveness) and by the unprecedented politicization of poverties and precariousness. The political logic that the 2011 insurrections emphasized shuns determinism and quickly gets rid of whoever pre-emptively wants to declare the end of it (wishfully hoping it to flow into the ballot boxes); instead, it looks to us that those insurrections opened future prospects that mark and continuously redraw the borders of a “continent of struggle”. One affected, with all their ambivalences, by unprecedented forms of refusal of and antagonism to the crisis, and explicit or implicit behaviours of antagonist solidarity and mutualism (it is enough to look at the social and political composition which began to show up starting with the Casbah of Tunis till Taksim Square).

The space on which the future prospects develop is not tied to the boundaries of the European Union. This is a given! It is all about following with profound realism the logic and the method of participating observation that guided Marx when, in the Class Struggles in France, he emphasized the issue of European space in the civil war in France. To get the point of that logic nowadays means also to avoid to give way to Eurocentric determinisms. And to reclaim a method to allow to stay firmly grounded to act among the desperation and the suffering that the first bite of austerity, called SalvaItalia decree, made millions of men and women in our society swallow. The results are obvious: there is the extraordinary uprising of October 19 and its important continuity, and there is a controversial December 9 that gives to the movements a bill of the earlier dynamics of radical impoverishment. And this is only to quote two of perhaps the most evident examples that refer to the deepening of the social perception of the crisis in the territories.

The great and blatant indifference about European elections and the enmity on which the relation between movements and European Union is based is a given of maturity, that strenghtens many political groups in conflict in Italy and elsewhere; able to listen to the territories where real struggles act and in which the earlier social behaviours of refusal and hostility against EU-austerity – to be understood in their ambivalence as well – develop. These territories, perhaps differently from Greece, are not informed at all by the modest ways and by the public opinion party of the Euro-Syriza, and from an antagonist point of view this is not a problem at all. On the contrary (!) it is a future prospect and a ground of solution; a sign that confirms – among the desperation and the suffering of the exploited – that the reduction to a calculated goal and to a minimal, politically pre-arranged outcome, can be never achieved. After all, if there are are no such things as Euro-struggles, a more or less latent “¡Qué se vayan todos!” shows up every time that a struggle breaks out. A yell that from one shore of the Mediterranean Sea to the other makes its way in search of a collective time and space to give again a “great leap”. To methodically work to its preparation, to build up territorial strenght and collective connection between the demands of social struggles, tenaciously keeping open the (transnational) future prospects, is what the antagonists are interested in, whether the Euro-debate likes it or not.

Infoaut Staff

[1] The Biagi Law finalized a ten year long process of precarization of the Italian labour market, producing a quantity of timed and discretionary contractual forms to the bosses’ advantage and greatly reducing workers’ rights and benefits.

[2] Our polemical target are the countless attempts, under a spate of different labels and electoral platforms, by the small leftist institutional parties and their power-hungry associates in the social movements to top-bottom represent autonomous social subjects and mass struggles. Their last effort was the “Main Way” platform last october (see the bottom hyperlink below).

[3] With “Orange mayors” we (as the mainstream media do) refer to a score of left-leaning elected mayors in 2011 and 2012, most notably in Milan, Naples, Palermo and Genoa. Hailing from civic networks and movements, and embracing global and national rampant anti-croniysm indignation, these mayors were elected in a protest vote against corruption and ineptitude of previous centre-right administrators and political vacuity of the moderate centre-left Democratic Party (which at times supported them). Later, having to cope with EU-imposed budget constraints and vested interests’ projects (such as the upcoming Expo 2015 in Milan), they had to forfeit their more progressive aims and awkwardly conform to austerity and pro-market measures.

The Bersani and Vendola ticket (respectively, chairmen of the Democratic Party and the small socialdemocratic Left, Ecology and Freedom party) was poised to win the 2013 Italian general election, but its lack of progressive appeal and inanity, in addition of an incongruous electoral law, produced a rump parliament and an anti-EU majority among the country voters.

[4] Repubblica, the main Italian daily and property of the Swiss billionaire and Democratic Party member Carlo De Benedetti, has been working steadily through the years to legitimize the party’s bids to power (often more effectively than the press releases of the party itself) and criminalize grassroots social movements. Its editorial group hosts the Italian branch of the Huffington Post as well and comments from leftist intellectuals such as Barbara Spinelli, daughter of the late Altiero Spinelli European founding father.

Ti è piaciuto questo articolo? Infoaut è un network indipendente che si basa sul lavoro volontario e militante di molte persone. Puoi darci una mano diffondendo i nostri articoli, approfondimenti e reportage ad un pubblico il più vasto possibile e supportarci iscrivendoti al nostro canale telegram, o seguendo le nostre pagine social di facebook, instagram e youtube.